As a young man of 27,

Frederick Douglass traveled to Britain to promote his new book on his life as a slave. His tour coincided with the Disruption of 1843 in Scotland when a third of the Church of Scotland withdrew and formed the

Free Church of Scotland. The financial need of the new church placed the Free Church in a position of needing contributions to support new churches and ministers. The moderator was the famed pastor & scholar,

Thomas Chalmers whos involvement in ministry to the poor and urban problems is still regarded with admiration today. Chalmers faced an immediate need to raise funds for the new denomination since it lacked state support. Donations from churches with slave-owners caused a controversy which provided Frederick Douglass to demonstrate the way in which slavery corrupted everything it touched. At the conclusion of his nineteen-month speaking tour of Ireland and Britain, Douglass emerged a confident and authoritative leader of the abolitionist movement.

|

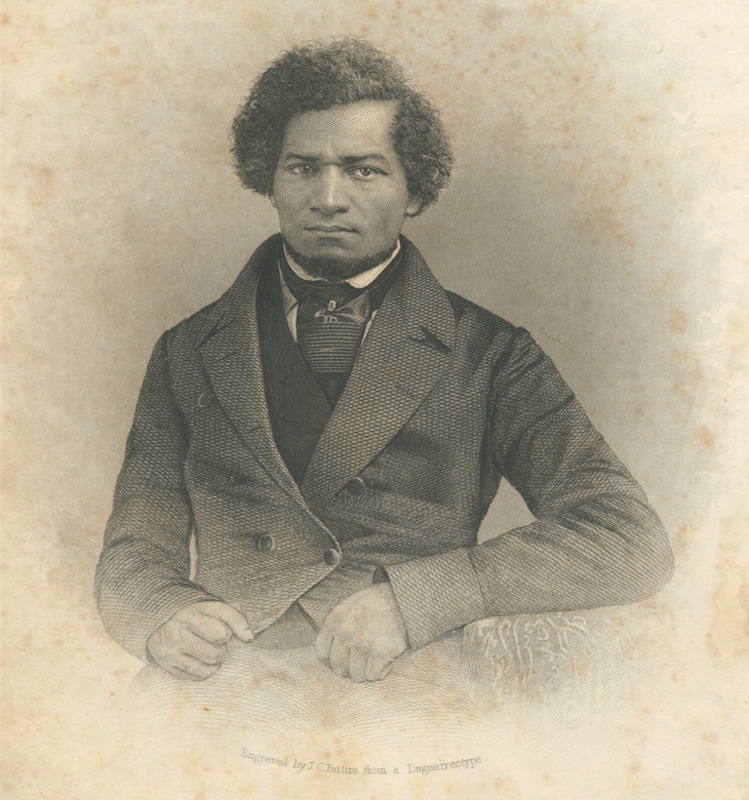

| Frederick Douglass |

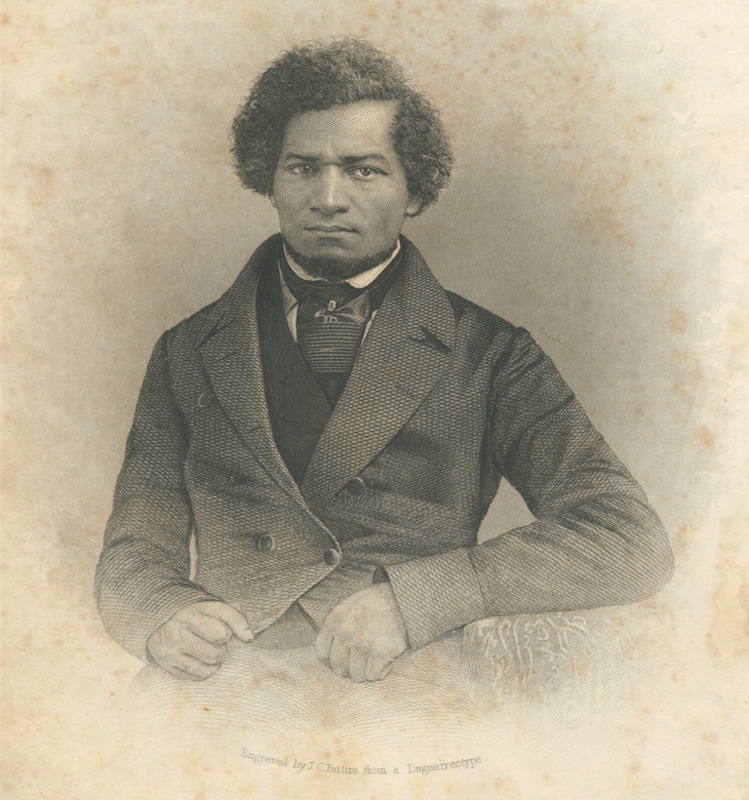

Frederick Douglass was the most renowned and

celebrated African- American of the 19th century and remains one of

the most influential Americans in the history of the United States. With the

publication of David Blight’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography renewed interest

in the life and impact of Douglass continues to grow. Born in 1817 a slave in

Maryland, Douglass escaped in 1838 to Massachusetts eventually joining the

abolitionist movement with William Lloyd Garrison. Douglass quickly rose in

prominence within abolitionist circles where his oratory and intellect

confounded those who argued that slaves lacked the mental abilities to

contribute as American citizens.

|

| Frederick Douglass in his 20s about the 1840s from Wikipedia |

With the publication of his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass in 1845, the celebrity of

Douglass spread as an illustration of the cruelty of slavery. In attempt to

widen his influence and expose the cause of abolitionism to an international

audience, Douglass traveled to the British Isles for a period of nineteen

months for a series of speaking tours which not only increased his prominence

but also involved Douglass within the debates within Britain and especially

within the newly formed Free Church of Scotland. (For details of Douglass' travels in the British Isles see the excellent website: Frederick Douglass in Britain and Ireland) While the vast majority of

British evangelical Christians proclaimed slavery a sin, the debate remained

regarding how Christians and churches needed to treat Christian slave-owners

and those profiting from the slave trade. A special concern was the ecumenical

relationships between Protestant churches in the South and their counterparts

within Britain and Ireland. British Christians began to ask how they ought to

regard Southern Christians with whom they shared confessional and theological

convictions while Southerners insisted upon their right to hold and promote

slavery. At the time of Douglass’ tour, a fierce debate arose within the Free

Church of Scotland which also involved Thomas Chalmers, one of the most eminent

Presbyterian preachers and theologians of the Nineteenth Century. This paper

will examine the debate within the Free Church of Scotland over its response to

slavery and Douglass’ involvement within the debate. The participation of

Frederick Douglass in a debate consuming Scotland contains a certain irony

since Douglass picked his surname due to inspiration from Sir Walter Scott’s

poem, Lady of the Lake.

The fact that Douglass selected a name derived from a poem bursting with

Romanticism and chivalry remains quite intriguing since Douglass previously

escaped the slave culture of the South enamored with the romanticism and

gallantry of Sir Walter Scott.

Douglass’ own inherent romanticism is obvious when he describes his friend

instrumental in the name choice, Nathan Johnson as a stalwart hand and an

illustration of the noble virtues described by Scott.

By 1843 the Church of Scotland ruptured over a

debate which consumed the church for over ten years. Division within the church

split the Church of Scotland into two camps, the Moderate or Establishment

faction, who wished to safeguard the traditions of the Kirk

and the Evangelical party who focused upon evangelism and missionary

opportunities. Sunday Schools, gospel meetings, missions, and other opportunities

for Christian education were activities generally frowned upon by The establishment wing of the church but actively promoted by evangelicals.

The evangelicals continually pressed for the spiritual independence of the

Church against the power of the state while the Moderate party found common

cause with the Tory party which maintained that the interest of landowners

required protection. The

issue which led to the division within the Kirk was the issue of patronage. Patronage

allowed the landowner to appoint the minister to the local parish church, often

with the local congregation having no participation in the decision.

Traditionalists remained committed to patronage while evangelicals saw

patronage as a political intrusion of political power over ecclesiastical

authority. The decade long conflict culminated in the withdrawal of over one-third of the ministers of the Kirk at the 1843 General Assembly of the Church

of Scotland in Edinburgh. The Great Disruption led to 451 ministers leaving and

752 ministers remaining in the Kirk. The number of elders and members who withdrew

from the church was one-third of the total membership.

After presenting a protest to the Assembly, the protesters withdrew and walked

to nearby Tanfield Hall where the new Assembly elected Thomas Chalmers the

first moderator of the Free Church of Scotland. While patronage was a principal

cause of the fragmentation, other theological issues also triggered division

and threatened the establishment between Church and State.

These issues were not unique to Scotland but appeared within Protestant

denominations within Germany, Netherlands, and the United States where

theologically reformed denominations became especially vulnerable in the

struggle between theological preciseness and cultural leadership.

|

| The Disruption Assembly by David Octavius Hill from Wikipedia |

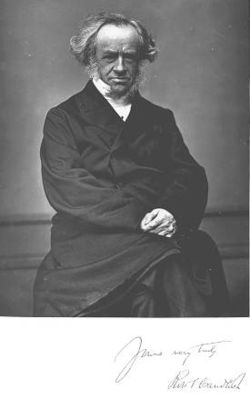

Thomas Chalmers was the recognized leader of the

Evangelical party before the disruption and after the withdrawal leadership

naturally fell into his hands. Thomas Chalmers was the leader of the

Evangelical wing of the Kirk and one of the most popular preachers in Britain.

His abilities spread to other areas such as science, math, and economics having

taught in the sciences at the University of Edinburgh. Chalmers believed in the establishment of the

state church and the responsibility of the state to support the Church but he

maintained that the state possessed no authority over spiritual matters.

While Chalmers believed that the state had no voice in the matters of the

state, he actively proposed programs to aid the urban poor. As the pastor of

the St George's Tron Church, in Glasgow Chalmers built schools, established

Sunday Schools, and instituted an aggressive parish visitation program. He

charged his deacons with ministry to the poor, using church funds to assist the

poor. Each situation was subject to investigation with the goal of finding ways

to help families with family and neighborly sources used before the church or

state resources. Chalmers wanted aid to become based upon charity and personal

relationships rather than an impersonal right.

Only after all avenues such as possible employment and family assistance

reached an impasse were the poor given a stipend from church funds. Chalmers

saw charity as an integral Christian principle and his methods were very

similar to the methodology used many years later by professional social

workers. While

Chalmers’s ideas on addressing poverty never eliminated state involvement in

social welfare, his ideas led to the growth of his church and changed the work

of the church as “more than the activity of the minister.”

But Chalmers’s reputation as a theologian and a preacher elevated his fame as

one of the most celebrated preachers of his age. Lectures given in 1938 held

London spellbound as his biographer Stewart Brown shares,

The rooms in Hanover Street where

Chalmers delivered the lectures were 'crowded to suffocation' with members of

England's governing elite, including royal princes, prelates of the Church of

England, great nobles, leading statesmen, and MPs from both parties.

The fame of Chalmers spread to

North America as his sermons and lectures as his published works found

readership in Canada and the United States and relationships began to grow

between churchmen on both sides of the Atlantic.

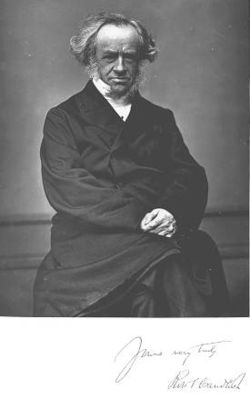

|

| Thomas Chalmers from Wikipedia |

As

moderator of the newly formed Free Church, Chalmers faced a dilemma. His

greatest problem was financial. The new church lacked the ability to completely

support itself monetarily even with large fundraising campaigns within

Scotland. Conscious that the split raised awareness in the United States, the

Free Church sought to raise funds from associates in the new world. Soon after

the creation of the Free Church, Chalmers appointed five men to serve as

delegates to churches in the U.S. Dr. Robert Burns, Dr. William Cunningham,

Rev. William Chalmers, Elder and merchant Henry Ferguson, and Rev. George Lewis

received a task to present the mission and vision of the newly established Free

Church of Scotland. The Scottish delegates sought out familiar friends and

looked to strengthen ties to pastors and churches with similar theological

convictions. The envoys were not to actively request for money but there was an

underlying expectation of financial assistance as the delegates toured

sympathetic churches.

But Chalmers was unlikely unaware that ties with American and especially

Southern churches placed an American debate over slavery within the center of

the Free Church of Scotland.

The

delegation split upon arriving in the United States with each member visiting

different areas of the country. William Cunningham took a special interest in

theological education in the United States, so he spent considerable time

visiting Princeton College then the center of Old School Presbyterian

education. George Lewis covered the most territory and left the most complete

record of his visits and interactions. In his Impressions of America and the American Churches, Lewis shares his experience and thoughts on the U.S. and

American churches. His observations about slavery reveal a disappointment in

the way Americans excused their tolerance of a practice that even many Americans

viewed as sinful. He believed along with most modern historians that Slavery in

the United States was less cruel than the slavery of the West Indies he

revealed frustration at the pace of American attitudes toward slavery. Lewis

appreciated an 1818 General Assembly resolution that declared slavery “as a

gross violation of the most precious and sacred rights of human nature; [and]

as utterly inconsistent with the law of God,

but still, Presbyterian leaders avoided the subject of slavery and even in Princeton

no one would not call slavery sin in spite of living in a free state.

Lewis clearly expressed his disappointment,

The

General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church some years ago voted slavery to be

“great moral evil;” but no practical step has yet been taken by it, as a

church, towards its extinction, although many such lie open before it. If

unprepared for the step of the Associate Reformed Synod, or even the Methodist

body, there lies at the door, crying for redress, not only the sin of slavery itself,

but the fruits of the sin of slavery- in the separation of husband from wife,

still legal- of parents from children the legal nullity of the marriage

relation- and the abominable legal prohibition, in many states, to teach the

negro to read and write. All these things lie unprotested against by the

General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. On these subjects they have never

once approached the legislature, or sought to rouse the moral sentiments of

their congregations. In these things, we say it with solemn regret, our

Presbyterian brethren in the States have come short of their duty. They dread

to approach the subject, or they touch on it in that language of apology and

mitigation which becomes not a Christian Church that has declared it “a great moral

evil,” and that should be pressing forward to its abolition. Even the

sentiments of the best men in the Presbyterian Church- of the Princeton

Reviewers- are unworthy of the high place its conductors justly hold in the

estimation of the Christian world.

In

response to the argument that Scripture allows slavery Lewis replied that the

Old Testament remained silent about polygamy and never discussed by Jesus but

the modern church never hesitates in denouncing multiple marriages.

In spite of his reservations regarding Southern slavery, Lewis remained

supported the fundraising effort in American and refused to join in the debate

over the legitimacy of accepting assistance from slave-owners.

![Robert Adamson, Rev. George Lewis, 1803 - 1879. Of Dundee and Ormiston; Free Church minister; editor of the Scottish Guardian [a]](https://www.nationalgalleries.org/sites/default/files/styles/postcard/public/externals/108743.jpg?itok=O0FSFR_Z) |

| Rev. George Lewis from the National Gallery of Scotland |

Most of the delegation except Lewis returned to

Scotland in time for the May 1844 Assembly of the Free Church. The envoys spoke

glowingly of the reception they received in the United States and the positive

attitude which Americans held the Free Church. Slavery was a subject mostly

avoided by the delegates as Cunningham stressed a desire to avoid controversial

subjects and being a stranger he had no intention in involving himself in

controversy. Even before the reception of American money

entered the discussion, pressure began to build for the Free Church to break

ties with slave owners and to refuse funds tainted with slavery. The GlasgowEmancipation Society sent a forceful ultimatum to the Church before the

delegation left for America that it refuse money sent by slave owners and that

the Church refuse fellowship with any American associated with slavery

At the 1844 Assembly in response to calls for an overture denouncing slavery a

committee formed under the leadership of Dr. Candlish with the task to report

its findings to an Assembly Commission. While

the committee denounced slavery, it hedged in its response on how to best address

the sin of slavery with churches in the American South. Candlish preferred not

to pronounce judgment on the Southern Presbyterians so the committee denounced

slavery in general while claiming ignorance regarding the circumstances of the

Southern churches. The committee refused to take any action which might

interfere in the relationship between the Free Church and American churches.

The report of the committee satisfied no one. The report offended Southern

church leaders who felt stung by the denunciation of slavery, while

abolitionists believed the report neglected the main issue of slave-owners and

the continued sin of slavery.

The issue regarding collections received from slave-owning churches received no

mention from the committee and only served to inflame the issue. Estimates

revealed that the Free Church received at least $9000 from the United States

with one church in Charleston sending $2000.

And while the percentage of contributions collected from Southern churches was

a small percentage of the overall contributions the symbolic significance of

the donations became the center of a massive debate inside and outside the Free

Church.

|

| Dr. John Duncan from Wikipedia |

The issue of aid received from

slave-owners became a concern which began to dominate the Free Church. Slavery

grew into a moral question which greatly concerned Christians of different

denominations and many Christians throughout Britain participated in

anti-slavery organizations. The World Anti-Slavery Convention met in London in

1840 and declared that it was the “incumbent duty” of Christian Churches to

disallow all slave-owners from participation in the Lord’s Supper and in the

following years a number of denominations declared it the duty of Christians to

fellowship with slave-owners.

After the report of the committee led by Dr. Candlish, pressure continued to

mount from abolitionists for the Free Church to take action by returning money

sent by Southern churches. On 12 March 1845, the Free Church Presbytery of

Edinburgh

met and Dr. John Duncan of New College proposed an overture that proposed that

all funds received from churches with slave-owning members remain separate

until those churches repent. Dr. Duncan declared that the Church remain

uncompromising and he found it disbelieving that there were “ministers who

would sit down and eat the Lord’s Supper with such unmakers of men- of traders

in human blood.”

While Duncan’s overture represented a concern about ties with Southern

churches, Cunningham and Candlish quickly worked to eliminate support for

Duncan’s overture. Cunningham continued an oscillating position which condemned

slavery in general while offering cover for individual slave owners. He

maintained that slave-owning provided no barrier to fellowship in the ancient

church and that like Christians of the Roman Empire found that slavery was a

weight forced upon them. The opposition of Cunningham and Candlish effectively

squashed the overture suggesting that the presbytery allow the matter to

proceed to the forthcoming General Assembly. Near the end of the Assembly, Dr.

Candlish gave the report of his committee which reinforced the principle that

slavery was a “heinous sin” and that the American churches were reluctant to

face the sinful nature of slavery. He rejected any effort however to cease

relationships with American churches with slave-owning members. Candlish

concluded that a continued relationship offered the opportunity for,

“faithfully exhorting and admonishing them to a full discharge of their duty.”

He encouraged the Free Church to continue the relationship with the American

Church so as to exhort with Christians he said, “are placed in such difficult

circumstances, in order that they may be found faithful.”

The Assembly accepted the committee report from Dr. Candlish in an effort to

maintain unity and put the issue behind the church.

|

| Rev. Robert Candlish from Wikipedia |

While the failure of the Free Church

to break ties with the American Church over slavery caused great concern for

abolitionists, the report of the committee caused concern and a sense of

betrayal from Southern churches who previously hosted Free Church delegates. In

a letter to his friend Dr. Thomas Chalmers containing a £332 gift, Dr. Thomas Smyth the pastor of Second Presbyterian Church of Charleston, SC expressed hurt

over the supposed condemnation contained in the committee report. Regarded as a

moderate on slavery in Charleston, Smyth strongly supported humane conditions

and religious education for slaves and his assumption that in time God might

ordain the end of slavery offered a less forceful defense of slavery than many

slavery apologists.

His letter to Chalmers revealed Smyth’s sense of disloyalty from a church he

demonstrated generosity towards and a fear that increased hostility towards

slavery from Scotland threatened the relationship between

Southern Presbyterians and the Free Church. Born in Belfast, Smyth received an

education in London and then traveled to the United States with his parents

where he obtained a ministerial training at Princeton. When he became pastor in

Charleston, Smyth had a large number of international contacts including

Chalmers and leaders who later led the Free Church.

While

Smyth had the reputation as a moderate defender of slavery, Chalmers took a

moderate stance against slavery. In 1814 Chalmers signed a petition arguing

that the abolition of the French slave trade become one of the conditions of

any peace treaty between Britain and France. He was friends with a number of

Members of the Clapham Sect such as William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson who

campaigned for the abolition of slavery within the British Empire.

In 1826, Chalmers wrote a short pamphlet, AFew Thoughts on the Abolition of Colonial Slavery which advocated for a

gradual emancipation within British territories. Chalmers’s pamphlet sets out a

strange and naïve plan whereby the slave earns his own freedom by working

during his free time.

the

slave who idled his free time, whether in sleep or in amusement, would of

course make no further progress towards a state of freedom,. He would live and

die a slave because he chose to do so. They from whose liberty most danger is

apprehended, because of their idle or disorderly habits, would, by the very

tenure on which it was held out to them, be debarred forever from the

possession of it.

While

considered a strong advocate for the impoverished, Chalmers did not advocate

for abolitionism with the same passion but because of his reputation as an

ecclesiastical leader, numerous social reformers and abolitionists sought his

support. But, after the disruption, the financial burden of keeping the Free

Church of Scotland supported consumed Chalmers and strained his health.

While the most generous contributions to the Free Church came from New York,

Chalmers believed that more contributions were available in the South if only

there were more delegates to send to Southern churches.

There is little evidence that Chalmers responded to pleas from abolitionists

but he did respond to letters from Thomas Smyth. While many letters remain

lost, the threat to Christian unity appears to be a concern for both. Smyth

expressed his hurt over the comments by some in the Free Church of no “fellowship

with slaveholders” and Smyth wanted a response from Chalmers of his opinion on

slavery.

Smyth wrote in ,

And

now, my dear Sir, judge of the pain and grief with which I have received

accounts of certain proceedings, in Glasgow and Edinburgh in which representatives

of the Free Church took part & in which there is a glaring want of all

courtesy, not to say Christian charity… But I will hope in a few weeks to see

you on the subject in the hope that you will exert your mighty influence to

prevent the adoption of a course which however gratifying it may be to

ultraists could not commend you moderation for calm & thinking &

devotion to Christians.

Chalmers’s

response to Smyth demonstrates the attempt by Chalmers of his moderate tone toward

slavery,

I

do not need to assure you, how little I sympathise with those – because slavery

happens to prevail in the Southern States of America – would unchristianise

that whole region. And who even carry their extravagance so far as to affirm,

so long as it subsists, no fellowship or interchange of good offices should

take place with its churches or its ministers. As a friend to the universal

virtue and liberty of mankind, I rejoice in the prospect of those days when

slavery shall be banished from the face of the earth; but most assuredly the

wholesale style of excommunication, contended for by some, is not the way to

hasten forward this blissful consummation.

Smyth

allowed the letter from Chalmers wide exposure and after Chalmers death in

1847, Smyth composed a eulogy which contained Chalmers’s rebuke toward the

abolitionists Smyth regarded as radical. While most Southerners felt stung by

any criticism of their use of chattel slavery, abolitionists in both Britain

and America felt that Chalmers’s response to Smyth compromised the Free

Church’s stance on Southern slavery. In a response, Chalmers composed an

article in the Free Church paper The Witness. While affirming that slavery

was a great evil, Chalmers continued to maintain that there was a difference

between “the character of a system and the character of the persons whom

circumstances have implicate therein.” Chalmers remained unwilling to break

fellowship with churches or Christians associated with slavery. He maintained

that even “zealous abolitionists” would own slaves if placed in the same

situation. Chalmers admitted to the corrupting vices often associated with

slavery but insisted that slave-owning did not inevitably lead to corrupting

vices.

Chalmers’s writings reveal a man hopeful to put the divisive issue of slavery

behind the Free Church. He neither wanted to break ties with Southern

slave-owners in the Presbyterian Church nor stay out of step with the

anti-slavery attitude within Scotland. As Smyth communicated to Chalmers in

April 1844, he shared Smyth’s outlook and “the hope that Christians could get

on with preaching the gospel unfettered by prejudice executed by external

influence.”

But the likelihood of putting the issue of slavery and the use of contributions

from Southern churches behind the church became impossible for with the

appearance of Frederick Douglass in Britain in 1845, the question of slavery

began to consume the Free Church of Scotland.

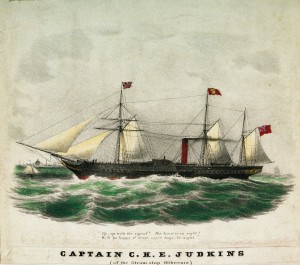

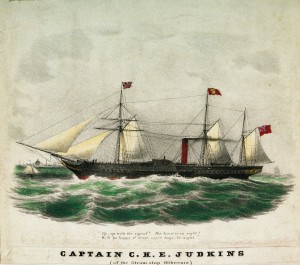

|

| The steamship Hibernia of the Cunard line the sister ship to the Cambria the ship Douglass sailed to Britain (National Maritime Museum) from History Ireland |

Frederick Douglass left for Ireland

and Britain in August 1845 with the purpose of promoting his new memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass released in May 1845 and quickly sold five thousand

copies. Douglass also wanted to strengthen ties with the abolitionist movement

in Britain and isolate Southern slave-owners from international society. He

proclaimed that he wished to “encircle America with a girdle of Anti-slavery

fire.”

Douglass traveled with James Buffam an abolitionist and wealthy carpenter and

the Hutchinson family singers who often provided singing at abolitionist

events. Douglass and his party boarded the Cambria for an eleven-day journey

across the Atlantic. Douglass found himself denied a cabin and assigned to

cheaper steerage accommodations but their excitement allowed Douglass and

Buffam to count the room as a “victory for thrift.

But the discrimination continued even after the reassignment of berths for

Douglass found himself excluded from the public eating but also the religious

services aboard the ship. He wrote to Garrison,

I

was not only deprived of eating in the saloon, but also shut out from religious

worship. We had two Sundays during the voyage, and in conformity to the

religious ideas of the Company, as well as of the British public, had regular

religious services performed on board. They called upon ‘our Father,’ the Creator of the heavens and the earth-the God who

has made the blood all nations, the black

as well as the white- to bless

them- while they cursed and excluded me on account of the color of my skin.

This I thought, was American slaveholding religion, under British colors, and I felt myself no great loser

by being excluded from its benefits.

Afterward,

Douglass reports no slights or discrimination other than the ignominy

previously suffered but remarks about the politeness and attention he received

from the officers but describes the indignity forced upon him as a form of

coercion. Douglass clearly points the prejudice heaped upon his person because

of race as the “difference between Freedom and slavery.”

Without any more incidents, Douglass arrived in Liverpool on August 28 and then

two days later journeyed to Ireland on a ferry.

Douglass received a warm welcome in

Ireland and conducted a wide-ranging speaking tour throughout Ireland for six

months. Douglass enjoyed a substantial popularity among Irish women as

anti-slavery offered Irish and British women an opportunity for political

involvement that lacked the impression of threatening the contemporary social

order.

Douglass constantly fought back the impoverished conditions of the poor Irish

with the conditions of American slaves. But Douglass still experienced great

empathy and identification with the Irish. He witnessed beggar children,

desperate adults with amputated limbs, and oppressed hungry people in the first

period of the Irish Potato Famine.

In a letter to Garrison, Douglass expressed the horror of the suffering he

witnessed,

I

am not only an American slave, but a man, and as such, am bound to use my power

for the welfare of the whole human brotherhood. I am not going through this

land with my eyes shut, ears stopped, or heart steeled.

But

still, Douglass insisted on the differences between a slave and the impoverished

Irish. While the suffering of the Irish was real they were not enslaved.

During his visit to Belfast Douglass

began to recognize the importance of the controversy over contributions from

Southern churches to the Free Church. Belfast was an important center of public

opinion due to a large number of Presbyterians in Northern Ireland and the

migration of Northern Irish to the Southern states.

But Northern Ireland was beginning a

rapid industrialization with a growing middle class, especially among the Presbyterians.

The Irish of Belfast earlier worked to abolish slavery in the empire and often

sent memorials to Presbyterians on the sinfulness of their practice of chattel

slavery.

The expanding middle class shared many of the same reform concerns as other

Victorians in Britain giving Douglass a receptive audience. His success in

Belfast convinced Douglass to remain in the city for an extended time as copies

of his book sold rapidly

Douglass’ reception in Belfast also

coincided with the arrival of Thomas Smyth to his birthplace in Belfast. Douglass

support of the growing “Send Back the Money” campaign was certain to bring him

in conflict with Smyth. Smyth’s goal for visiting his homeland was to settle an

inheritance from an aunt in Dublin and attendance at the Evangelical Alliancein London. Smyth deeply desired an alliance between American and British

evangelical Christians. But Douglass urged his Irish and British listeners to

hold American slave owners and sympathizers accountable for if they defended

slave owners they were defending the men “who scourged his female cousin until

she was crimsoned with her own blood from her head to the floor.

Further, Douglass revealed his intent to encourage British Christians to break

fellowship with American slaveholders. Douglass used Scripture itself and

logic to turn the tables upon Southern slavery. As reported in his

encouragement to an audience in Belfast,

He

could not see how the slaveholder could say that portion of the Lord’s prayer

which said, ‘Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them who trespass against

us.’ To use such a prayer would be praying not to forgiven. It would be calling

down curses instead of blessings on the head of the slaveholder who would use

it. How could the man who held his fellow-man in bondage read that portion of

the word of God which says, ‘Do unto others as you would they do unto you,’ and

still keep him fast bound in chains?... The slaveholder should be made to feel

that the practices in which he was engaged were reprobated by all good men.

(Cheers) He trusted the voice of that large ad respectable assembly would cross

the Atlantic-that it would be heard by the slaveholder, and that he would feel

that a Belfast audience execrated him on account of his connection with the

horrible system of slavery.

Douglass shattered the concept of the Christian

slave owner declaring that one could ‘not serve, God and Mammon” and accused

slaveholders of blasphemy by associating their oppression with the “meek and

lowly Jesus.” Douglass used biblical morality and stories to challenge the

consciences of his audience. With the arrival of both Smyth and Douglass

in Ireland, both soon became aware of each other’s presence in Ireland with

Douglass challenging Smyth to meet him and challenge his facts.

During the General Assembly of the

Presbyterian Church of Ireland, slavery was a primary topic and many in the

body wished to break fraternal relations with the American Presbyterian Church

but realizing that this prevented future reprimands the Assembly sent a

censure. Normally Smyth’s presence warranted recognition but as Smyth wrote,

“found that the introduction of my name into the Assembly would lead to

excitement and unpleasant remarks and by my request withheld it.

The presence of Douglass and the

clamor in the Assembly over slavery effectively isolated Smyth. Frustration

with the denunciations led Smyth to label Douglass an infidel and to repeat

gossip accusing Douglass of visiting a brothel. These accusations were

especially cutting in the setting of Victorian society and held the possibility

of fatally damaging Douglass’ reputation in Britain. Douglass demanded an

explanation from Smyth in a letter but received no response. Afterward, Smyth

received a visit from a childhood friend Robert Bell and another minister Isaac Nelson who both asked for evidence or a retraction. Unsatisfied Bell wrote to

Smyth,

Your

conduct in relation to Douglass, a poor fugitive slave, in retailing and

circulating vile hearsay calumnies against him, and the fact of Rev. McCurdy

totally denying the statements you imputed to him, leaves me at a loss to know

what to think.

The rumors

spread as Pastor Richard Webb reported that,

in

Belfast a Carolinian Rev. Smith, a Methodist, endeavored to injure Douglass by

calumnious reports” and that in parody of the Send Back the Money! slogan the

town was placarded with large bills demanding Send Back the Nigger! This could

have come from nobody but this diabolical minister of Christ.

After procuring communication from Bell forsaking

their friendship, Smyth also received on the same day communication from

Douglass’ solicitors that unless Smyth provided an explanation or retraction

then he could expect a libel suit. Then Smyth was served with a write of ne exeat regno forbidding his exit from

the country. When

pressed for an explanation, Smyth claimed that he repeated reports from Rev.

Mr. McCurdy and Joshua Himes, a Boston Adventist and abolitionist. The whole

affair became a farce as a Rev. Samuel McCurdy was located, denied involvement,

and warned Smyth to keep his name out. Another McCurdy informed Douglass’

solicitors that he never communicated directly or indirectly with Smyth. Finally,

Smyth located a John A. Mcourdie, who he claimed as his source but by then

solicitors from all parties arranged an apology from Smyth to Douglass. Smyth

conveyed,

for certain statements made by me

injurious to his moral and religious character, and express my sincere regret

for having uttered the same: the more especially as, on mature reflection, I am

quite satisfied that the statement I incautiously made on the report of third

parties were unfounded.

The upheaval over slavery in the Irish Presbyterian

Church and the conflict with Douglass humiliated Smyth but delighted Douglass

who admitted the trouble he caused Smyth. He confessed to an American friend,

I am playing the mischief with

the character of slave holders in this land. The Rev. Thomas Smyth D.D. of

Charleston, South Carolina has been kept out of every pulpit here. I think I

have been partly the means of it. He is terrible mad with me for it.

|

| Dr. Thomas Smyth of Charleston from Presbyterians of the Past |

When

Douglass arrived to Scotland the debate over slavery was fierce and the “Send

Back the Money!” campaign was in full swing and he intended to take complete

advantage of the debate to draw a complete picture of the cruelty of slavery

and isolate Southern churches with slaveholders from British churches. Douglass

possessed a special appeal for Scotland having taken his surname from SirWalter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake and his arrival there seemed to increase

his fascination. In a letter to Francis Jackson he shared,

almost every hill, river, mountain, and

lake of which has been made classic by the heroic deeds of her noble sons.

Scarcely a stream but has been poured into song, or a hill that is not

associated with some fierce and bloody conflict between liberty and slavery.

The Scottish also appeared to have an equal

fascination with Douglass. While he was not the first former slave to speak

publicly in Scotland, Douglass regaled the Scottish with stories of his youth

and peppered his speech with satire and mockery of slave owners. His portrayal

as the David against the Goliath of slavery swept the audience into cheers of

approval. Rev.George Gilfillan, a literary minister was so enchanted with Douglass that he offered

a tribute to him in his published lecture, The

Debasing Influence of Slavery on All and Everything Connected to It,

You have yourselves witnessed a signal

and splendid instance of what a powerful idiosyncrasy growing amid the most

unfavourable circumstances can effect. You have seen in Frederick Douglass a

man whom slavery had not nipped but developed-whom the struggle with the

elements has not only newed but expanded- whom I may almost denominate a

suicidal birth of the monster, born and nursed, educated and endowed to destroy

his cruel and unnatural mother.

The Free Church debate offered Douglass an

opportunity to impress Scottish audiences the need for the Free Church and

Britain to disassociate itself with slavery. In a speech in Glasgow, he

expressed his desire to encircle America about a cordon of Anti-slavery

feeling- bounding it by Canada on the north, Mexico on the west, ad England,

Scotland, and Ireland on the east,” with the message to the slaveholder that he

is “a man-stealing, cradle-robbing, and woman-whipping monster.”

Douglass recognized the importance of the “Send Back the Money!” crusade

writing to his friend Francis Jackson,

The

present position of the Free Church of Scotland makes it important to expend as

much labor here as possible. You know they sent delegates to the United States

to raise money to build their churches and to pay their ministers. They

succeeded in getting about four thousand pounds sterling. Well, our efforts are

directed to making them disgorge their ill-gotten gain- return it to the

Slaveholders. Our rallying cry is “No union with Slaveholders and send back the

blood-stained money.” Under these cries, old Scotland boils like a pot.

Through the

winter and spring of 1846 the “Send Back the Money” campaign kept Scotland

boiling. Placards, flyers, and flags appeared at abolitionist rallies and

street corners. On a huge hill looming over Edinburgh sympathetic Scots carved

in large bold letters, SEND BACK THE MONEY!

Even songs featuring the campaign satirized the position of the Free Church. A

number of broadsheets with poems poked at the Free Church and the trouble

caused by the money. One of the most powerful songs was set to the tune of

Robert Burn’s poems, “A Man’s a Man for a That.” This particular song must have

delighted Douglass since he revered Burns as one who stood against powerful

forces and hypocrisy.

The song challenges the Free Church for taking funds stained with blood and

gotten through fraud and deceit. The mention of “ the negro’s God” that slaves

were also children of God. It challenges the Church to send the money back

“without delay.”

Send back the

money, send it back, tis’ dark polluted gold

T’was wrang from

human flesh and bones by agonies untold

Theres no a mite

in a’ the sum but what is stained wi’ blood

Theres no a mite

in a’ the sum but what is cursed by God.

Send back the money, send it back, partake not in

the sin

Who buy and sell and trade in men, accursed gains to

win

Theres no a mite in a’ the sum an honest man may

claim

Theres no a mite but what can tell of fraud, deceit

and shame.

Send back the money, send it back, tempt not the

negro’s God

To blast and wither Scotland’s church wi his

avenging rod1

Theres no a mite in all the sum but cries to heaven

above

For wrath on all who shield the men who trade in

negro’s

blood.

Then send the money back again

and send without delay

It may not, must not, cannot

bear, the light of British day.

Some

songs mentioned Douglass, indicating the impact he bore on the debate and the

pressure felt by the Free Church leadership. The Send back the Money song

challenges Chalmers (Tammy) with building the Church with the blood of slaves. (to hear a sample of some of the anti-slavery songs sung follow the link to Bulldozia)

I’ve heard a

voice on thunder borne, my boy Tammy

I’ve seen the fingers

raised in scorn, my boy Tammy

Heaven rings wi’

Douglass’ appeal,

An’ thrills my

heart like burning steel

An’ conscience

racks me on the wheel,

Ye’ve wranged,

ye’ve grieved yer Mammy.

Shall I, as free

as ocean’s waves,

Shake hands wi’

women whipping knaves

An’ build Kirks

wi’ the bluid o’ slaves,

Send back, SEND

BACK THE MONEY!

Douglass’ logic and biblical imagery continued to

challenge the leaders of the Free Church. He challenged the Free Church with

laying a foundation for the church by “following the bidding of slaveholders…

whilst they turn a deaf ear to the bleeding and whip-scorned slave.” Douglass

challenged George Lewis to debate and while Lewis refused Douglass still

satirized and created a dialogue with Lewis over his willingness to take money

from the profit of slavery. If Douglass’ old master Mr. Auld had responded to

Lewis’ need by selling one of his slaves he would say to Lewis, “I’ll tell you

what I’ll do. I have a fine young negro who is to be sold, and I will sell him

tomorrow and give you the contribution to the cause of freedom,” all while

“brother Lewis prays and reads Blessed are those who give to the poor.”

Douglass amidst great cheers begins a refrain of “Send Back the Money.”

When

the Church says did not Abraham hold slaves? The reply should be, Send back

that money! When they ask did not Paul send back Onesimus? I answer, Send you

back that money! That is the only answer which should be given to their

sophisticated arguments, and it is one that they cannot get over. In order to

justify their conduct they endeavor to forget that they are a church and speak

as if they were a manufacturing corporation. They forget that a church is not for

making money, but for spreading the Gospel. We are guilty, say they, but these

merchants are guilty and some other parties are guilty also. I say, send back

that money. There is music in the sound. There is poetry in it.

Douglass even challenged Thomas Chalmers still

venerated by most when he responded to the argument that Southern slave-owners

lacked the ability to release their slaves without breaking the law. Douglass

cried, “If the law were to say that we were to worship Vishnu or any heathen

deity would that be right because it was the law?”

Chalmers claimed that while slavery was evil, he viewed slavery in the same

category as war. One could be a Christian soldier then so one might be a

Christian slave-owner. Douglass mocked the distinction Chalmers made between a

sinful system and the character of a person within the system.

Oh!

The artful dodger! What an excellent outlet for sinners! Let slave-owners

rejoice! Let a fiendish glee run round and round through hell! Dr. Chalmers,

the eloquent Scotch divine, has, by long study and deep research, found that .

. . while slavery be a heinous sin, the slave-owner may be a good Christian,

the representative of the blessed Saviour on earth, an heir of heaven and

eternal glory, for such is what is implied by Christian fellowship.

In

addition, Douglass never hesitated to challenge the Free Kirk over its use of

the word Free Church while collecting the fruit of slavery. During his entire

tour of both Scotland and England Douglass continually pressed against the hypocrisy of churches who tolerated slavery using the language and imagery of

Scripture.

The Free Church met for their 1946 General Assembly

in May at Cannon Mills in Edinburgh and slavery was on the top of the list of topics

for the Free Church due to memorials received from the Glasgow Emancipation

Society and the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society as well as a

remonstrance from the Edinburgh Ladies Emancipation Society. By the time of the

Assembly, the leadership cooled the question of American slavery and never

seriously considered calls for returning money back to Southern churches. Rev.James Macbeth argued differently. He reasoned since previous efforts with the

American Church was fruitless, Macbeth proposed,

This

Assembly hearby resolves that this church cannot admit to its pulpits, or to

the communion table, any individual in the United States by whom slavery is

practiced, nor can receive deputations from any church which does not visit

slave-holding members with excommunication; and this resolution this church

adopts in the spirit of love towards the churches that are implicated in this

sin.

But Macbeth never received a second on his motion,

Dr. Candlish responded negatively and maintained that “no one is disposed to

second the motion by Mr. Macbeth.” Dr. Cunningham concluded with a lengthy

exposition by making a distinction between the sin of slavery and the

individual born into a system of slavery. Further Cunningham strongly rejected

the charge of heresy leveled against the Southern churches saying, “You cannot convict

them of any heresy in regard to their abstract opinions respecting slavery . .

. you can only say there is much that is erroneous and defective in their

impressions and mode of action”

Cunningham reasoned any attempt to cut off ties between the Free Church and the

American Church over slavery was the path of radical abolitionism which he

completely rejected.

|

| Dr. William Cunningham from Wikipedia |

Douglass observed all the proceedings personally and

sat at a distance to witness the debate. Douglass saw first-hand the excitement

of the campaigns as he said the Send Back the Money slogan covered the city.

Like many abolitionists, he viewed the decisions by the Free Church at the General

Assembly a sinful equivocation and compromise with slavery that the Free Church

acknowledged as evil and sinful. Douglass believed the Church lost an

opportunity to proclaim justice and demonstrate repentance. He summarized,

The

deed was done, however; the pillars of the church—the proud, Free Church of

Scotland—were committed and the humility of repentance was absent. The Free

Church held on to the blood-stained money, and continued to justify itself in

its position—and of course to apologize for slavery—and does so till this day.

She lost a glorious opportunity for giving her voice, her vote, and her example

to the cause of humanity; and to-day she is staggering under the curse of the

enslaved, whose blood is in her skirts. The people of Scotland are, to this

day, deeply grieved at the course pursued by the Free Church, and would hail,

as a relief from a deep and blighting shame, the "sending back the

money" to the slaveholders from whom it was gathered.

Douglass

took full advantage of the controversy over contributions from slave owners and

the ensuing campaign to publicize the plight of slaves in America. He believed

his meetings in Scotland were successful and that the campaign with the Free

Church allowed him a platform to open the eyes of the Scottish people to

slavery. While the goal of persuading the Free Church to send the money back to

Southern churches, the role of Douglass in the debate brought him to the

forefront of the issue and revitalized Scottish abolitionists societies.

Douglass left Scotland knowing that he accomplished changes,

One

good result followed the conduct of the Free Church; it furnished an occasion

for making the people of Scotland thoroughly acquainted with the character of

slavery, and for arraying against the system the moral and religious sentiment

of that country. Therefore, while we did not succeed in accomplishing the

specific object of our mission, namely—procure the sending back of the money—we

were amply justified by the good which really did result from our labors.

Douglass continued his extensive tour of Britain

speaking constantly as he covered the country during his last six months in

1846-47. He returned to Scotland in September 1846 joined by William Lloyd

Garrison and continued to criticize the actions of the Free Church General

Assembly. Douglass continued to attack the fine distinction Scottish clergy

wanted to between the individual slaveholder and the system of slavery which

they labeled sinful. He also condemned the excuse given to Southern slave

owners beholden to the law. Douglass quickly pointed to the hypocrisy of the

Free Church traveling to America for money when state laws prohibited teaching

slaves to read and write. Preventing slaves from reading the Bible was a

serious issue and Douglass pointed how the laws in the Southern states impeded

the gospel and contrasted with Free Church missionary practice, “You might

carry them (Bibles) to Hindostan and circulate them there but you cannot

circulate them amongst the slaveholders.”

Giving individuals the ability to read the Bible was an important fruit of the

Protestant Reformation. But the idea that Southerners must obey the state law

rather than the Biblical mandate to give the Scriptures to their slaves

revealed the hypocrisy behind Southern churches and the refusal of the Free

Church to disfellowship from churches with slave-owners. Douglass pointed out

the deception saying,

I

heard at the Free Church Assembly speeches delivered by Duncan, Cunningham, and

Candlish, and I never heard, in all my life, speeches better calculated to

uphold and sustain that bloody system of wrong. (Cheers) I heard sentiments

such as those from Dr. Candlish – that Christians would be quite justified in

sitting down with a slave-holder at the communion table- with men who have the

right, by the laws of the land to kill their slaves. That sentiment, as it

dropped from the lips of Dr. Candlish was received by three thousand people

with shouts of applause.

Referring

to Dr. Cunningham’s General Assembly speech which removed fault from Christian

slave-owners for obeying the law Douglass wryly observed, “let us suppose the

law should make all domestics the concubines of their employers- that he would

be bound to sustain the relation, would he do it?” His rhetorical question

answered itself because Dr. Cunningham “believes it to be wrong, and that it

would not be sustained by the morality of the religious sentiment of Scotland

for a moment.”

In a farewell speech given in Londonon March 30, 1847, shortly before his departure, Douglass thanked the British

people for their hospitality and continued to expose the hypocrisy of American

slavery. He continued his similar theme of bringing to light the hypocrisy of slave-owning within a Christian and republican society,

I am going to the United States in a few days,

but I go there to do, as I have done here, to unmask her pretentions to

republicanism, and to expose her hypocritical professions of Christianity;

to

denounce her high claims to civilization, and proclaim in her ears the wrongs

of those who cry day and night to Heaven, How long! how long! O Lord God of

Sabaoth! … In the state of Virginia…will not allow her black population to meet

together and worship God according to the dictates of their own consciences. If

they assemble together more than seven in number for the purpose of worshipping

God, or improving their minds in any way, shape, or form, each one of them may

legally be taken and whipped with thirty-nine lashes upon his bare back. In all

the slave states south, they make it a crime punishable with severe fines, and

imprisonment in many cases, to teach or instruct a slave to read the pages of

Inspired Wisdom. In the state of Mississippi, a man is liable to a heavy fine

for teaching a slave to read. In the state of Alabama, for the third offence,

it is death to teach a slave to read. In the state of Louisiana, for the second

offence, it is death to teach a slave to read. In the state of South Carolina,

for the third offence of teaching a slave to read, it is death by the law. To

aid a slave in escaping from a brutal owner, no matter how inhuman the

treatment he may have received at the hands of his tyrannical master, it is

death by the law. For a woman, in defence of her own person and dignity,

against the brutal and infernal designs of a determined master, to raise her

hand in protection of her chastity, may legally subject her to be put to death

upon the spot. (Loud cries of “Shame, shame.”)

I

have now been in this country nineteen months, and I have travelled through the

length and breadth of it. I came here a slave. I landed upon your shores a

degraded being, lying under the load of odium heaped upon my race by the

American press, pulpit, and people. I have gone through the wide extent of this

country, and have steadily increased—you will pardon me for saying so, for I am

loath to speak of myself—steadily increased the attention of the British public

to this question. Wherever I have gone, I have been treated with the utmost

kindness, with the greatest deference, the most assiduous attention; and I have

every reason to love England.

Sir,

liberty in England is better than slavery in America. Liberty under a monarchy

is better than despotism under a democracy. (Cheers.) Freedom under a

monarchical government is better than slavery in support of the American

capitol. Sir, I have known what it was for the first time in my life to enjoy

freedom in this country. I say that I have here, within the last nineteen

months, for the first time in my life, known what it was to enjoy liberty.

Earlier Douglass considered moving his family to

Britain to escape the legal status of a Maryland slave. The desire to make

Britain his home faded but the worry over his legal status increased. A number

of his British admirers led by his friends Emma and Mary Richardson began

efforts to contact his former owners the Aulds to buy Douglass’ freedom.

Through intermediaries, Douglass received his freedom for 150 pounds sterling

or $711.66. While he received congratulations from friends, he also became the

subject of accusations of paying a ransom deal. Many abolitionists denounced

the exchange of money which granted Douglass’ freedom claiming he lost his

power as a fugitive slave but Douglass rejected the claim. He proclaimed, “I

shall be Frederick Douglass still; and once a slave still. I shall neither be

made to forget, nor cease to feel the wrong of my fellow countrymen still in

chains”

During the spring of 1847 and after nineteen months in Britain, Douglass

boarded the Cambria and journeyed

home. After fifteen days he arrived home in Boston harbor on April 20, 1847, and

soon rejoined his family in Lynn, Massachusetts.

The debate over slavery and the

relationship with slave-owning church members in America with the Free Church continued

after Douglass’ departure from Britain. Soon after the 1846 Free Church General

Assembly, a number of members formed The Free Church Anti-Slavery Society with

the short-range goal of isolating and disfellowshipping with slave-owners and

the long term goal of emancipation. However, the leadership of the Free Church

continued to strengthen their resolve on the issue of slavery even as The church received a number of petitions decrying the position of the Free Church

in its relationship with American churches. The 1847 General Assembly quickly

dismissed the petitions and Dr. Cunningham refused to yield that any church

which admitted slave-owners was guilty of heresy. Such an admission entailed a

rupture in the fellowship which Cunningham refused to allow. Cunningham concluded

with angry words, claiming that the dispute was “an ingenious device of Satan

to injure the church,” and accused “the Garrisons, the Wrights, the Buffens,

the George Thompsons, and the Douglasses” as tools of division. Further, he

claimed that any man of good principle, good sense, and good feeling, who has

any professed regards for Christian liberty, will soon abandon altogether any

connection with it.”

Cunningham’s speech essentially shut down the debate, and while there were

written responses, the death of Dr. Thomas Chalmers diverted the attention of

the Assembly away from slavery. The Assembly suspended all business for a day

and the death of Chalmers hovered over the remainder of the Assembly. Debates

over slavery effectively ended with the 1847 Assembly as the 1848 Assembly

ignores the slavery question.

The Send Back the Money campaign

revealed a great divide within Scotland over slavery. Almost all Scottish

churches believed that slavery was sinful but, most possessed a conflicted conscience

regarding the response of the church to slavery. The response of the Free

Church leadership toward the Send Back the Money campaign and Southern slavery

reflect the moderation and refusal of Chalmers to label slave-owners sinful.

Denominational loyalty and insecurity over the Disruption caused most churchmen

reluctant to criticize the stance of the church over its relationship with

Southern slaveholding churches.

The Send Back the Money campaign

ultimately failed as the leadership and most of the membership rejected any

efforts to return funds to Southern churches or to break ties with the American

church over membership of slave owners. Chalmers and Cunningham remained

convinced that ecclesiastical ties to the American church were too important to

break in spite of the issue of slavery. Their reasoning that Southern

Christians found themselves bound by the law regarding slavery left them with

no options was flawed reasoning. The Free Church leaders held that Southern

Christians suffered under laws made by legislatures but they failed to express

fully the involvement of Southern Christians in the laws which forbade

education for slaves and proscribed harsh treatments. Southern Presbyterians

were leading citizens involved in all areas of society including politics. The

status of state laws governing slavery was due not just because the Churches

failed to pressure the state but many prominent politicians were complicit in

the injustice of the laws.

Chalmers and the Free Church leaders also failed to fully understand that their

actions provided legitimacy for Christians profiting from slavery. Their fine

distinction between an evil system without placing responsibility or accountability

on the individual Christian placed a distinction between communal sin and

individual sin and accountability which appeared contrived and hypocritical.

The use of Chalmers’s words by Thomas Smyth in the Southern Presbyterian Review

shortly after Chalmers’s death provided encouragement to Southerners and

revealed a common antipathy toward the abolitionist’s cause.

Our

understanding of Christianity is, that it deals with persons and wit

ecclesiastical institutions and that the object of these last is to operate

directly and approximately with the most wholesome effect on the consciences

and the character of persons. In conformity with this view, a purely and

rightly administered church will exclude from the ordinances NOT ANY MAN, AS A

SLAVE-HOLDER, but every man, whether slave-holder or not as licentious, as

intemperate, as dishonest. Slavery, like war, is a great evil- but as it does

not follow that a slave-holder cannot be a Christian, neither does it follow

that there may not be a Christian slave-holder… Neither war nor slavery is

incompatible with the personal Christianity of those who have actually and

personally to do with them. Distinction ought to be made between the character

of a system and the character of the persons whom circumstances have implicated

therewith.

Chalmers

ability to personal sins and societal ills allowed Smyth and others to excuse

the present issue of slavery into a category which granted cover to church

members profiting from chattel slavery. Smyth gladly used Chalmers as a witness

against the abolitionist’s “furious fanaticism of popular and ecclesiastical

abolition outcry.”

Chalmers’s words to Smyth provided useful to Southern slave-owners and

apologists in three ways. First, it placed slavery in a category of societal

evils which allowed Southerners to profit from without threatening their

personal holiness and secondly, Chalmers like many Southerners placed

abolitionists into a radical class whose words and actions were best ignored.

Finally, Chalmers’s reinforced the doctrine of the spirituality of the church

which taught that the church remain silent on issues which Scripture was

silent. Many Southern pastors and theologians used the spirituality of the

church to prevent the church from issuing judgments on slavery. The Doctrine

of the Spirituality of the Church became one of the chief instruments Southern

churchmen used against a growing chorus of criticism from the North and the

world.

Frederick Douglass was not the first

architect of the Send Back the Money Campaign but he took full advantage of the

campaign to publicize the horrors and corrupting nature of chattel slavery. Douglass

realized that a Christian could not simply separate slavery into a separate

category and still maintain Christian holiness. He understood that slavery

corrupted everything it touched and caused great suffering among slaves.

Douglass’ oratorical abilities and skill enraptured the British and Irish but

in spite of his great speeches and logic, the campaign never convinced the Free

Church to return any American contributions and sever ties with slave-owners.

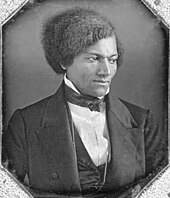

The immediate goal of the campaign was a failure. But Douglass’ British tour

became an essential part of his success. Douglass was a young man of twenty-seven when he left the USA for Britain, but after his time in Britain, he left

a self-confident man with the faith that the abolition of slavery was possible.

With the help of friends, Douglass returned to America a free man and with a

gift of two thousand pounds, Douglass had the ability to break from the

paternalistic grasp of Garrison and found his own paper The North Star. In

Britain, Douglass spoke to thousands and intermingled freely with host of

British high society and intellectuals. When Douglass arrived in Boston Harbor

on April 20, 1847, he was the most famous black man in the world.

|

| Frederick Douglass from Wikipedia |

Bibliography

Chesnutt,

Charles W. Frederick Douglass. edited by Ernestine Pickens,

Atlanta: Clark Atlanta University Press, 2001.

Goodlad,

Lauren M.E. ""Making the Working Man like Me": Charity,

Pastorship, and Middle-Class Identity in Nineteenth-Century Britain; Thomas

Chalmers and Dr. James Phillips Kay." Victorian Studies 43,

no. 4 (2001): 591-617.

Maclear,

J.F. "Thomas Smyth, Frederick Douglass,and the Belfast Antislavery

Campaign." The South Carolina Historical Magazine 80, no.

4 (October 1979): 286-97.

Noll,

Mark A. "Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) in North America (Ca.

1830-1917)." Church History 66, no. 4 (December 1997):

762-77.

Ritchie,

Daniel. "'Justice Must Prevail': The Presbyterian Review and Scottish

Views of Slavery, 1831-1848." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 69,

no. 3 (July 2018): 557-84.

Ritchie,

Daniel. ""The Stone in the Sling": Frederick Douglass and

Belfast Abolitionism." American Nineteenth Century History 18,

no. 3 (2017): 245-72.

Roxborogh,

John. "The Legacy of Thomas Chalmers." International Bulletin

of Missionary Research (October 1999): 173-76.

Shepperson,

George. "Notes and Documents:Thomas Chalmers, The Free Church of Scotland,

and the South." The Journal of Southern History 17, no. 4

(November 1951): 517-37.

Claire Puglisi Kaczarek, “Thomas Chalmers(1780-1847) and

the 1843 Disruption: From Theological to Political Clash,” Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology 24, no.1, (2006):

20-21.

![Robert Adamson, Rev. George Lewis, 1803 - 1879. Of Dundee and Ormiston; Free Church minister; editor of the Scottish Guardian [a]](https://www.nationalgalleries.org/sites/default/files/styles/postcard/public/externals/108743.jpg?itok=O0FSFR_Z)