.jpg)

The legend of Sparta captures the

imagination of many through literature and movies. The image of a society

dedicated to the military and warfare fascinates even amateur historians. Concrete information about Sparta is limited. Definite details about the lives of women in Sparta are

even less certain. On Sparta

by Plutarch is one of the primary sources which provides details about the monarchy and culture of Sparta. Sarah Pomeroy

uses Plutarch as one of her sources in her book, Spartan Women.

|

| Spartan Women by Sarah B. Pomeroy |

Pomeroy scrutinizes the sources and

presents a fuller portrait of many facets of the women of Sparta. Sarah Pomeroy,

born in 1938, attended Barnard College and earned her doctorate at Columbia

University. She is presently retired after many years of teaching at Hunter

College in New York City and remains a

leading authority on the lives of Greek and Roman women. Her sifting through the

sources presents Spartan women as distinctive when compared to the rest of ancient

Greece. The women of Sparta simply possessed more influence than other Greek women.

Pomeroy divides her work into organized

sections which feature different aspects

within the lives of Spartan women. The first three chapters deal chronologically with the routines of the

women. Starting with “Education,” “Becoming a Wife,” and “The Creation of

Mothers,” Pomeroy lays out the topics important for women and girls. The final

three chapters examine, “Elite Women,” The Lower Classes,” and “Women and

Religion.” She offers a concluding section which summarizes her points and

examines Spartan ethnicity through the issues of gender. The volume also offers

a detailed appendix which provides extensive data on her sources.

| Ancient Greek city-states from www.ixl.com |

Within most of Greece, there were limited educational

opportunities provided for women. Literacy was important for the male citizens

of Athens because democracy demanded an educated citizenry. Literacy was unavailable for the women. The

opportunities for Spartan women differed from their Athenian sisters. The

opportunities for education among the ladies and girls of Sparta exceeded those

of other Greek women. Women trained in

public speaking and “were encouraged and trained

to speak in public, praising the brave, reviling cowards and bachelors.” (9) Verbal

skills link to the necessity of literacy. Poetry and philosophy became an

interest for Spartan females and while there are no existing examples of their

work their effort in the arts continued into the Hellenistic period. Physical

education and music were also educational foundations of female education in

Sparta. There was a religious link to music and athletics as these activities coupled

with religious festivals. Athletic competition and horsemanship

were opportunities for women as part of the physical education system

established by Lycurgus. Nudity was also a component of sporting events as

girls competed either nude or wore a peplos

(tunic) with an exposed breast. (25)

|

| Spartan Woman Bronze Statue from Ancient History Encyclopedia |

Eugenic

principles greatly influenced the suitability of male babies as Sparta

regularly practiced male infanticide by exposing unsuitable baby boys to the

elements. There is no evidence that female children faced elimination through

exposure as adult women cared for female infants.

Spartans placed great emphasis upon marriage,

and they used many novel methods for spousal arrangements. Young adults often

paraded in the nude during festivals which provided potential spouses a

complete view of potential partners. It's possible that Spartan women had the

opportunity of practicing polyandry as multiple fathers provided help in

childcare. But it appears that Spartan society used numerous options in

producing children including wife-sharing or husband-doubling. (40) Illegitimacy

was not a fear for Sparta as long as all participating adults consented. An examination

of Spartan martial arrangements reveals that women were active participants in

the marriage process.

Spartan living

arrangements gave women a leadership forum within the Oikos. Men usually dined with the other men in the syssition. Therefore women remained in charge

of the food dispersal. (52) The diet of Spartan women even surpassed that of

the men since men and boys were responsible for adding to their rations. The

nourishment provided to Spartan females was of such quality that Xenophon

remarks on it. (52)

Upon marriage, relationships

faced numerous issues which reduced fertility. The prevalence of homosexuality

reduced the number of children as men engaged in sex with other men when women

refused the men sex. The regulations of Lycurgus placed strict limitations on

the number of visits newly married couples could receive. It is probable that

Spartan ignorance regarding fertility and frequency of intercourse decreased

the number of children born in the first few years of marriage.

Mothers also were

highly influential in the lives of their sons. Spartan women took great pride

in a son who distinguished himself in battle. But Spartan mothers also were

“renowned for enthusiastically sacrificing their sons for the welfare of the

state.” (57) Mothers would not abide a son who abandoned his post or exhibited

cowardice. A son who disgraced his state with cowardice might face death from

his mother. A mother could assume the power of the state and kill her son if he

fled the battlefield. Aristotle objected to the power of Spartan women when he

observed that women often dominated their sons and even their husbands in

certain situations. (69)

Many ancient societies

believed that a woman who refused childbirth was unpatriotic. Sparta valued so

highly mothers that only men who died in battle and women who died in

childbirth received gravestones. (52) A good example of an assertive mother was

Gorgo who emphasized the special role of Spartan women when asked about the

power of Spartan females. A woman from Attica asked her, “Why is it that you

Spartans are the only ones who can rule men?” Reportedly her answer was, “That

is because we are the only ones who give birth to men.” When an Ionian visitor

bragged about her special weavings, a Spartan woman responded by showing off

her “four well-behaved sons” as the product of a “noble and honorable woman.”

(135) Spartan society recognized the importance and contribution of their women,

and this appears in the power and recognition given to their females.

Sources provide more

information on the elite women than helot or doulai (slave) women. Land

allotments were more favorable to Spartan women than other Greek females. Most lands

fell under the control of the state and women. Because the women of Sparta lived

longer, they often controlled the land as heiresses. Reforms also allowed women

ownership of property and land. Aristotle drew attention to the huge number of landowning

heiresses and the presence of oliganthropia (sparse male citizen population). Wealthy

women gave elite females a voice in the household and society. Aristotle

noticed this as well when he took notice that women had a larger role in

aggressive and warlike societies. (92)

|

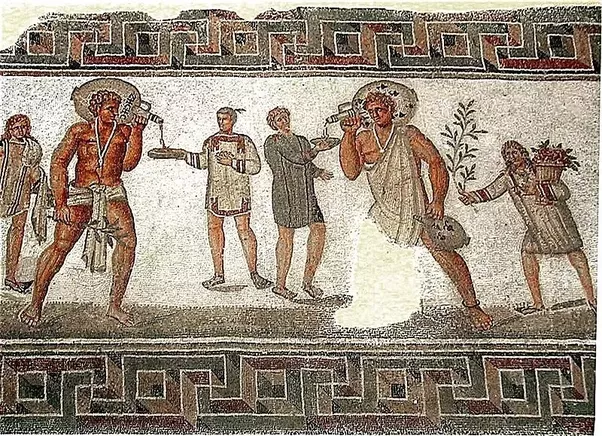

| Helots from Medium |

Lower class women

present a challenge for the historical sleuth. Several classes of people

outside of citizens lived in Sparta. The helots were farmworkers essential to

Spartan society since Spartan citizens did not engage in agriculture. The

helots functioned as slaves of the state but were allowed to live as a family

in housing. Helots served at the pleasure of citizens, and any citizen could

murder one for little cause. Some helots served in the military and became

parents of half helot children. Mothakes, children of Spartan fathers and helot

mothers might rise to recognition from their fathers and achieve freedom.

Other residents also

added to the variety of Sparta. Free non-citizens or periokoi were free residents but not citizens. They engaged in crafts,

as merchants, and sometimes agriculture. Other women also worked in the

community. Spartan nurses had a high reputation and were often employed by

foreigners. Lower than helots were the

douloi or slaves who often served in

households. Doulai women often weaved cloth and clothing for the household.

Women were also closely

engaged in the religious cults and rituals and played an integral part in the propagation

of the faith. Women took an active part in song, dance, feasts, offerings, athletics,

chariot processions and weaving for idols. (106) The Greek pantheon contained

numerous goddesses and many of the rituals and festivals centered on female deities.

Artemis was an especially important fertility goddess who protected women and

children. She was also closely associated with another nature goddess Orthia.

Women actively participated in music, dancing, and celebration. Leaden figures

from the seventh and sixth centuries demonstrate women playing flutes, lyres,

and cymbals. Tales of abduction also feature during the festival and rituals may

express the condition women find themselves when leaving their secure families

only to arrive in the insecurity of a new marriage. (107) Other festivals and

ritual centered on a wide variety of gods and goddesses with each having their

distinctive rituals.

|

Remains of the Menelaion from University of Warwick |

Especially important to

Sparta was the Menelaion, which was the shrine of Helen, Menelaus, and Helen’s

brothers Castor and Pollux. An interesting aspect of the Menelaion was the

evidence produced through archaeology that Helen was not subordinate to her

husband and even appeared independent of men. Similar to Artemis the worship of

Helen also consisted of music and dancing.(114) Spartans prized beauty among

females and Spartan women had a reputation for beauty among Greeks which may

explain the importance of the cult of Helen. Herodotus tells the story of a

deformed girl whose nurse carried her to the shrine of Helen begging for

Helen’s intervention. Helen appeared, and after Helen touched the child, she

grew into one of the most beautiful girls of Sparta causing quarrels among men

who pursued her. Her beauty was so great that the Spartan King Ariston made her

his third wife. (132-133)

Spartan women

understood the rules and standards of their society, but they had a greater

opportunity for participation than the typical woman of Greece. Spartan women

were not passive but took advantage of the many occasions for involvement and

leadership their society gave them. Women possessed power over their oikos often directing the nutrition and

affairs of the household. They participated in the denunciation of cowards and

even could bring death to their cowardly sons. Spartan women were outspoken and

gained a reputation among Greeks as not only beautiful women but as blunt and

forceful.

|

| Plutarch, On Sparta |

Pomeroy used numerous

sources in her research one of which was Plutarch. Plutarch was born in Greece

and later became a Roman citizen. He lived from about AD 46 to about AD 120 and

became known for his histories, essays, and biographies. His works include Parallel Lives and Moralia. Plutarch’s On Sparta

describes the lives of Sparta’s residents and the significant events of many of

the leading citizens. When read with Pomeroy’s Spartan Women, Plutarch provides a fuller picture of Sparta.

|

| Plutarch from Wikipedia |

Plutarch begins his

work with the legendary Lycurgus, often recognized as the lawgiver. Even Plutarch

recognizes the almost mythical status of Lycurgus, who possessed many

conflicting accounts of his life travels and death. Contemporary historians have

many doubts regarding the accounts of Lycurgus and recognize the difficulty of

placing him into the history of early Sparta. According to Plutarch, Lycurguswas responsible for many of the reforms which shaped Sparta. One of Lycurgus’

chief reforms was the formation of the Council of the Elders which was composed

of the Two Kings and twenty-eight of the citizens over sixty. The council acted

as a stabilizer between the tyranny of a monarchy and the chaos of democracy.

(8)He also redistributed the land and declared gold and silver invalid. With

the use of iron for currency, the practice of hoarding became impractical. The

introduction of common dining or messes increased comradeship and provided

opportunities for men and boys to bond. Perhaps the most monumental reforms were

the changes brought to the family. Lycurgus placed regulations upon newlyweds

and penalized those who did not marry. Above all children belonged to the state,

not to their fathers or mothers. Fathers brought children to a spot called the lesche where the male child received

confirmation of his worthiness. (20)

|

| Lycurgus from Wikipedia |

Agesilaus was the Eurypontid

king who came into office through remarkable circumstances. His father,

Archidamus had another son Agis by Lampido a noblewoman. Because Agesilaus was

not the heir, he brought up in the agoge,

where he received the training and severe lifestyle that young men and boys

faced. After his half-brother’s death, Agesilaus became king after the

legitimacy of Agis’ son Leotychidas came under question. The irony behind Agesilaus

as king was his imperfection. One of his legs was slightly shorter than the other,

but Agesilaus performed well showing a unique ability to relate to his men due

to his time in the agoge. Close to Agesilaus

was Lysander, his lover whom he knew from his time in the agoge. Agesilaus demonstrated great courage on the battlefield

refusing to retire from the battlefield until he saw the front despite his

great wounds. Along with Lysander, Agesilaus pursued an aggressive military

power, engaging in warfare until his death at 84.

By the time Agis IV

assumed the monarchy, Sparta had become greedy, and the state became flooded

with silver and gold. Agis expressed a desire to reform society and

redistribute land and eliminate debt. Due to the opposition, the ephors sentenced Agis to death by

strangulation. After Agis’ death, his brother Archidamus fled leaving Agis’

wife behind who was forced to marry Leonidas’ son Cleomenes. While Agis’ wife

Agiatis pleaded against a forced marriage eventually, she made Cleomenes “a

good loving wife.” It’s possible that Agiatis influenced Cleomenes in pursuing

the reforms of Agis. After the death of his father, Cleomenes assumed the

throne. Cleomenes after gaining confidence pursued the reforms proposed earlier

by Agis, yet the ephors were an

obstacle. Cleomenes removed the ephors by ordering their death. He began his

reforms by handing over his lands first and then followed by his father-in-law

Megistoous. Soon after others submitted their land, the land was divided

equally. He also reformed the agoge and

restored the training and messes. (106) After the defeat at the hands of the Macedonians,

Cleomenes face exile in Alexandria. His mother Cratesicleia and children faced imprisonment

by Ptolemy as ransom as a condition for his help. After Cleomenes committed

suicide, she faced death heroically, and Plutarch remarks that “during these

final stages Sparta played her role

through the prowess of women which was equally matched with that of men.” (131)

On Sparta also includes

a section of sayings by Spartans and sayings by women. These sayings reflect

the martial character of Sparta. For example, when questioned Agesilaus

about the lack of fortifications in

Sparta he responds by pointing to the armed citizens and simply saying, “These

are the Spartans’ walls.” (141) When a mother heard that her son was alive

after escaping the enemy, she wrote to him, “You’ve been tainted by a bad

reputation. Either wipe this out now or cease to exist.” (185)

| Cleomenes from Wikipedia |

Plutarch serves as an

effective complement to a reading of Spartan

Women. While Plutarch primarily examines the lives of important kings and

Lycurgus the lawgiver but the influence and importance of women are apparent

throughout. Lycurgus is careful in his instruction regarding marriage,

newlyweds, and family life because he believes the oikos and the polis must

maintain a balance. Homelife and marriage are important in the maintenance of

the state and a healthy family produce children who protect the state. Stong

women such as Agiatis and Cratesicleia were both instrumental in the reforms of

Cleomenes due to their great influence upon him. The stoic and honorable death

experienced by Cratesicleia remains as a memorial to Spartan women.

No comments:

Post a Comment