|

| John Lewis 1940-2020 from The Guardian |

John Lewis served over 30 years in the

US House of Representatives representing the Georgia 5th district.

His history as a civil rights leader and victim of a brutal beating while

crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge during a march for voting rights propelled

Lewis to a status as an icon. His long service in the House, stand for issues of

justice & racial reconciliation, and his willingness to befriend those on

the opposite side of the aisle brought him the reputation as the conscience of Congress.

Less

known was the campaign which won Lewis his long-held seat in Congress which

provided Lewis a national platform and transformed him into figure beloved by

Americans of every ethnicity and political persuasion. Lewis ran for the 5th District seat in 1977 after Andrew Young resigned to serve as President Jimmy Carter’s ambassador to the United Nations but Lewis lost his first bid for

Congress after losing the vote to Wyche Fowler. After a brief service in the

Carter administration, Lewis served six years as an Atlanta city councilor

until Fowler resigned his House seat to run and eventually narrowly win the election

to the US Senate. The campaign for the open 5th District seat

brought Lewis into conflict with another figure who also deserved the label as

an icon of the civil rights movement, Julian Bond, and a campaign long

remembered as a no holds barred political fight.

|

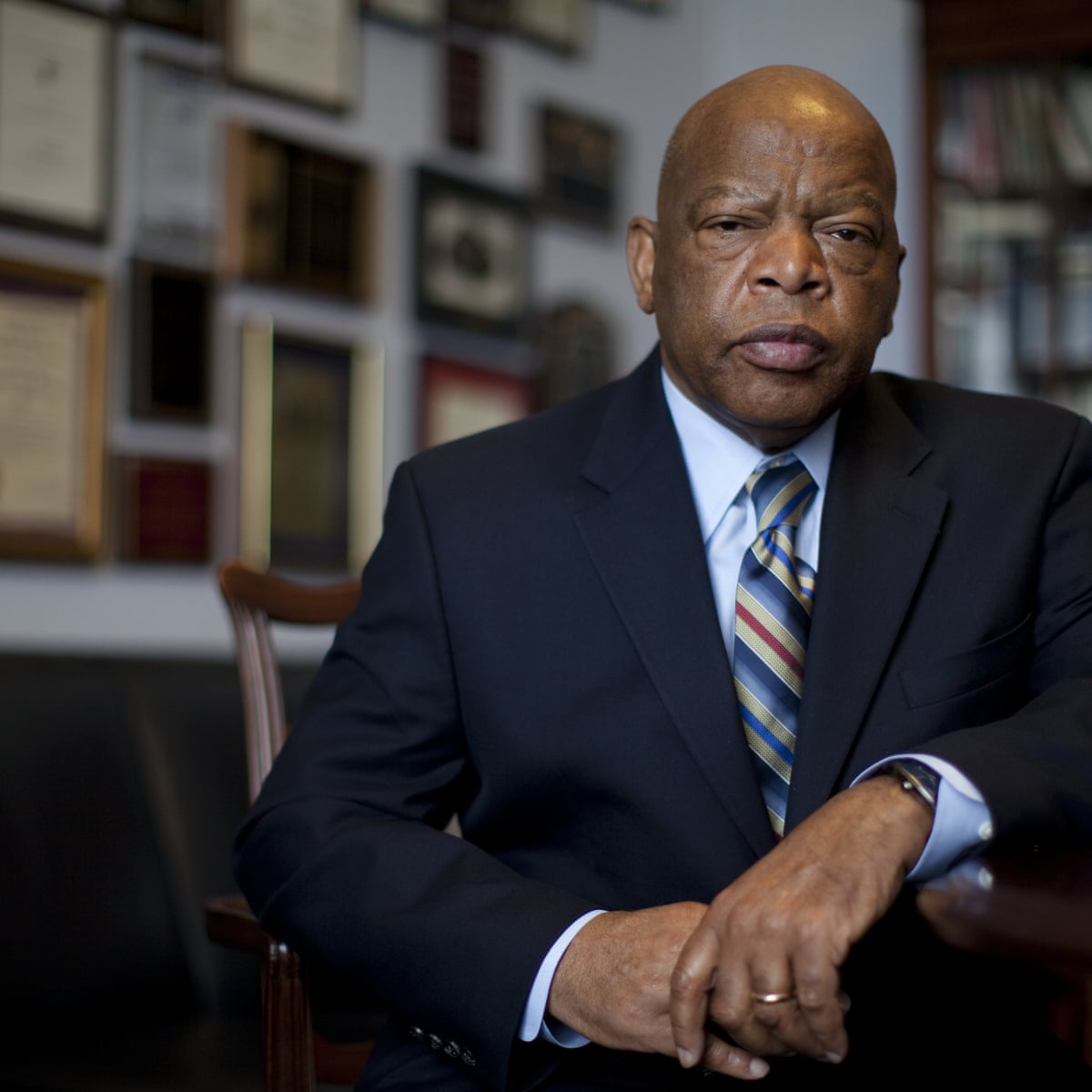

| Julian Bond & John Lewis from Society of US Intellectual History |

John Lewis and Julian Bond both

emerged into leadership during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and were

both co-founders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). But

while men shared leadership and friendship during significant elements of civil

rights, their backgrounds and experiences contrasted completely different backgrounds

of being black during Jim Crow segregation. Julian Bond was the son of

historian and university president Horace Mann Bond and Julian Bond enjoyed a

childhood surrounded by academics and exposure to intellectuals in what many

would describe as a life of privilege.

Bond describes his life,

My father got

his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He taught at a succession of black

colleges. He was president of Fort Valley State College, president of Lincoln

University in Pennsylvania, dean of education at Atlanta University. [At

Lincoln University,] we had this great big old white house like a Southern

plantation house. In our home were all the great figures of the day. I have a

picture of me sitting on Paul Robeson’s knee while Robeson sings to me. I have

a picture of Albert Einstein. It was just an incredible life for a kid. . . . I

never really knew what a segregated school was until high school. At George

School [a Quaker institution in Pennsylvania], I started dating this white girl

from Virginia. . . . We’d go into Philadelphia on Saturdays or Sundays, then

get back to school around 6 or 7 in the evening. Then one afternoon, the dean

of men called me into his office. . . . He looked like a tennis player or a

country club golf pro who had just begun to age. He told me, in a very calm and

polite voice, that he’d appreciate it if I didn’t wear my school jacket on

those trips to Philadelphia. It was just as though he had slapped me across the

face. All of a sudden, you realize all the talk there’s been, all the

whispering. . . . And also that you’re a Negro. That moment was the first time

I realize realized it—that distance. . . . I simply couldn’t speak anything to

him. I just stood up and walked out of his office.[1]

Bond

remained at the center of civil rights deciding to remain in Atlanta and served

over twenty years in the Georgia General Assembly and became a founder with

Morris Dees of the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama. After the election to the Georgia House of Representatives in 1965 Bond and seven other

black representatives faced opposition when white members of the Georgia House

refused to allow them to take their place in the House because of their

opposition to the Vietnam War. The Supreme Court forced the Georgia Assembly to

seat Bond declaring that the House denied him freedom of speech.[2] In

1968, he received a nomination for vice-president of the United States at the

Democratic National Convention in spite of at the age of 28 not meeting the age

requirement. Over time Bond grew adept at legislating eventually becoming the

chair of the Fulton County delegation and sponsored bills assisting poor

Georgians in obtaining home loans. Eventually, his years of effort helped to

create the Fifth District as the first majority-black congressional district in

Georgia, ironically the office he lost to Lewis. The handsome and urbane Bond

represented the future of black leadership and in 1977 when he hosted SaturdayNight Live, Bond presented an image of cool to the nation. Nationwide

appearances and speaking tours hinted at a bright future for Bond as some even

predicted that Bond would even reach the Georgia governor’s office.[3]

|

| Julian Bond & MLK from The New York Times |

John Lewis as the third child of ten

children of a sharecropping family was in many ways the opposite of Julian

Bond. Lewis experienced not only grinding poverty but the worst of Jim Crow

segregation as a native of Troy, Alabama. By the age of four, Lewis picked

cotton and peanuts just a few miles from the boyhood home of George Wallace.

Discrimination and injustice distressed Lewis,

My father couldn’t afford a newspaper subscription. I’d walk half a

mile to get my grandfather’s paper after he got done reading it. I kept up with

what was going on, reading that paper and listening to that radio. . . . We

ordered everything from the Sears & Roebuck catalog. We called it ‘the Wish

Book.’ . . . I was bused 18 miles to the Pike County Training School. Black

schools were ‘training schools’; whites went to high schools. We had old

broken-down buses, ragged books, a rundown building. White students had new

buses, nice painted buildings with the grounds kept up. . . . In Troy, they had

a soda fountain where you could get Coca-Cola. We called it a combination. A

black person could not take a seat. We had to stand at the end of the counter.

‘May I have a combination?’ You put your money down and went outside to the

street corner to drink it. . . . As a young child I saw a difference. I

resented it. Even the country road where I grew up—because black people owned

the land, the road was left unpaved for many, many years. When it rained, the

bus got stuck in the mud. That was life in Alabama.[4]

Inspired by the Montgomery bus boycott, Lewis

organized sit-in demonstrations while a student at Fisk University and later

became one of the original Freedom Riders. Lewis served as the leader of SNCC in

1963 and adhered strongly to a philosophy of nonviolence and reconciliation

during a tumultuous of confronting the worst evils of racism. Lewis emerged as

one of the important leaders and speakers during the March on Washington. On

March 7, 1965, Lewis endured a beating during the march from Selma to Montgomery

which fractured his skull and left scars he carried the rest of life.

|

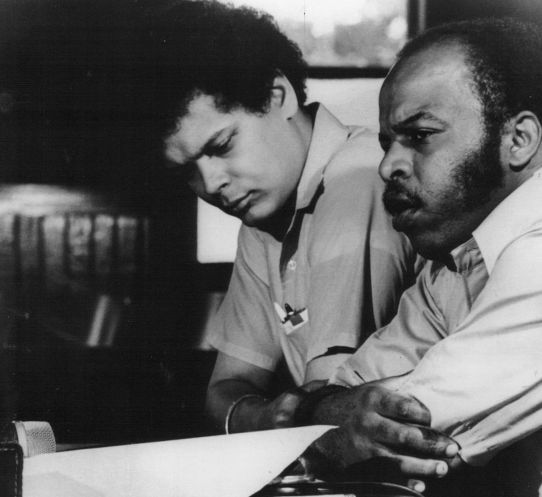

| John Lewis during his time on the Atlanta City Council from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution |

Despite

an old friendship rooted in the civil rights movement, Bond and Lewis faced an

intense and bitter Democratic primary campaign when both entered the race to

replace Wyche Fowler as the representative for the Georgia Fifth district. Because

the 5th district was overwhelmingly Democratic, a win in the primary

was equivalent to victory. Bond was the favorite of the black establishment of

Atlanta and received the important endorsement of Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young

who also formerly served as the representative of the 5th District. At

the time Bond was the greater celebrity and hosted fundraisers featuring

Washington mayor Marion Barry and jazz great Miles Davis. Bond felt entitled to

the seat, “I’d created the seat, drawn the lines myself, I’d made it possible

for a black person to be elected. I wanted badly to be there. I could see

myself there. It seemed natural to me, the next step.[5]”

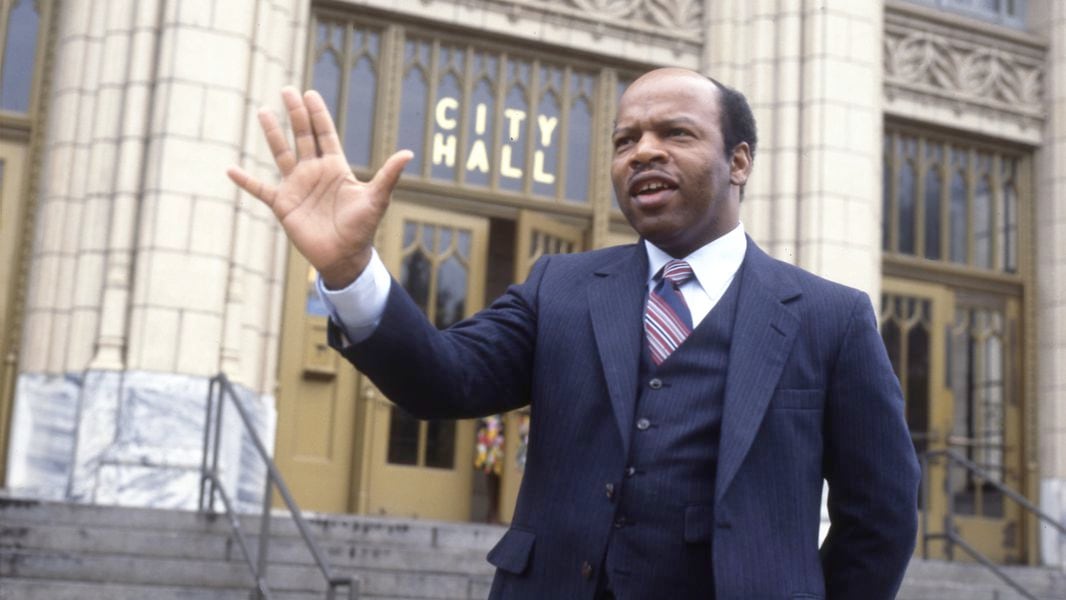

| State Senator Julian Bond shakes hands with his opponent City councilman John Lewis at a rally in 1986 |

Drug use

became a focus of the campaign when rumors spread that Bond engaged in drug

use. Lewis pounced on the issue and challenged Bond to take a drug test while

Bond accused Lewis of “McCarthyism and demagoguery.”[6]

During a debate, Lewis proclaimed that he passed his urinalysis test and came out

clean but Bond refused to take the test because it “trivializes the issue.[7]”

In black churches, the question arose on whether Bond was a man of faith as his

intellectual personality appeared off-putting to many. But it was the white

population whose mistrust of Bond became decisive in the election. Many of

Atlanta’s white liberal establishment mistrusted Bond and wondered out loud if

he would represent them in Washington. Although Bond was favored, the election

remained tight and Lewis defeated Bond in an upset. From the New York Times,

With all 241 precincts reporting in the unofficial count tonight, Mr.

Lewis had 34,548 votes, 52 percent of the total, to 32,170 votes for Mr. Bond. In

a race that badly strained relations in Atlanta's black community, Mr. Lewis's

margin of victory appeared to come from his strong lead in white precincts on

the city's north side, the last to be tabulated tonight. Mr. Lewis, endorsed by

the Atlanta newspapers and a favorite of the white liberal establishment and

neighborhood organizations, swept the white vote in the first primary, and Mr.

Bond captured the black vote. But in a district whose electorate is 58 percent

black, that division was almost enough to give Mr. Bond a majority. He got 47

percent to Mr. Lewis's 35.[8]

Defeat devastated

Bond and claimed whites cost him the victory he believed he deserved. The bitter campaign destroyed the friendship between

Lewis and Bond who wouldn’t speak to each other until 1989. Bond’s marriage dissolved

into bitter acrimony as his wife Alice publicly accused Bond of drug use although

she later recanted he accusations. After a divorce Bond left Atlanta and

relocated to Washington. He taught at American University and the University of Virginia. In 1998, Bond assumed the chairmanship of the NAACP after a scandal

rocked the organization. But many still felt that Bond never reached his full

potential and that he never really recovered from the defeat in 1986.

Lewis went on

to a storied Congressional career and came to be regarded as an American saint

due to his sacrifice at the Edmund Pettus Bridge and his role as the conscience

of Congress. But in spite of his present revered status, Lewis was still a

politician and his 1986 campaign demonstrated a willingness to engage in the

tough and dirty mud of a tough political campaign. His readiness to build

bridges in the 1986 campaign anticipated a congressional career that crossed

the political divide and work with Republicans even to build friendships with

those he disagreed. His touching tribute to Georgia Republican Senator Johnny Isakson

upon his retirement was just one testimony of the bonds developed by Lewis. But

Lewis also showed a willingness to lead protest when he felt the call and

participated in efforts to remind Congress and Americans of the unfished work

of civil rights. His doggedness led to the creation of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Lewis served long enough to see BarackObama elected as the nation’s first black president and in 2011 Obama awarded

him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Upon his death, Lewis became the first black man to have his body lie in state in the Capitol rotunda. And in spite of his many honors and

accomplishments, one must wonder the question of What If? If Bond triumphed in

the congressional election of 1986 might Bond have risen to become the

conscience of Congress and achieve the promise so many predicted in his youth.

|

| Memorial for John Lewis in the Rotunda |

Sources

Alzuphar, Adolf. "Julian Bond Vs. John Lewis:

An Unforgettable Fight For Atlanta’s Fifth Congressional District." Blavitv:News.

Last modified July 3, 2017. https://blavity.com/julian-bond-vs-john-lewis-an-unforgettable-fight-for-atlantas-fifth-congressional-district?category1=black-history&subCat=community-submitted&category2=community-submitted.

Clendinen, Dudley. "EX-COLLEAGUE UPSETS JULIAN

BOND IN ATLANTA CONGRESSIONAL RUNOFF." New York Times. Last

modified September 3, 1986. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/03/us/ex-colleague-upsets-julian-bond-in-atlanta-congressional-runoff.html.

Coppola, Vincent. "The Parable of Julian Bond

& John Lewis." Atlanta Magazine. Last modified March 1, 1990. https://www.atlantamagazine.com/great-reads/the-parable-of-julian-bond-john-lewis/.

Eversley, Melanie. "Voices: Bond's quiet

dignity commanded respect." USA Today. Last modified August 16,

2015. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/08/16/voices-julian-bond/31819723/.

Hallerman, Tamar. "John Lewis 1940-2020."

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Last modified July 2020. https://www.ajc.com/john-lewis-obituary/#chapter-1.

[1]

Vincent Coppola, “The Parable of Julian Bond & John Lewis”, Atlanta

Magazine, March 1, 1990, https://www.atlantamagazine.com/great-reads/the-parable-of-julian-bond-john-lewis/

[2]

Roy Reed,” Julian Bond, Charismatic Civil Rights Leader, Dies at 75,” The New

York Times, Aug 16, 2015

[3]

Copplola, March 1, 1990.

[4]

Coppola, March 1, 1990.

[5]

Coppola

[6] Dudley

Clendinen, “ Ex-Colleague Upsets Julian Bond in Atlanta Congressional Runoff”,

New York Times, Sep 3, 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/03/us/ex-colleague-upsets-julian-bond-in-atlanta-congressional-runoff.html

[7]

Clendinen

[8] Clendinen