|

| Gunhawks comic: from Wikipedia |

During my childhood and early teen years

I was an avid comic book reader. One particular fascinating comic book was a Marvel

Western series called Gunhawks. The

main character in the comic was a black gunslinger named Reno Jones along with

his childhood friend Kid Cassidy. Reno is a freed slave who lived a happy life on

the plantation with a kindly master where he and Cassidy grew up as friends.

But the Union Army attacked his home and the girl he loved. Rachel Brown became a captive of the Yankees and in response Reno joined the Confederate

army. At the end of the war, Reno and Kid Cassidy roamed the west on a quest to

find Reno’s lover Rachel. The publication of the Gunhawks comic was in the early Seventies but the Gunhawks was an example of a series of

stories that began after the success of the Civil Rights Movement which claimed

that the Confederate army had thousands of free blacks and slaves that fought

alongside white Rebel soldiers.

Today the proposition that the Confederate army included thousands of black rebels

soldiers remains a belief found in websites, Facebook groups, and even museum

exhibits. The increasing reach of the internet, amateur historical research,

and the desire to validate history for political and cultural purposes has only

led to the spread of claims that blacks participated in large numbers in the

Confederate forces. Heritage groups such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans

use the narrative of black Confederates as a vindication of their ancestors as

well as a tool to set them apart from white extremist groups. Kevin Levin in

his book, Searching for Black

Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth draws on primary source

documentation to annihilate the legend of black Confederates although he still

maintains that the labor of slaves became an essential element of the Confederate

ear effort. As soldiers marched to war, many brought body servants and other

slaves who served the army in a wide range of roles including cooking,

foraging, cleaning, and manual labor indispensable for a functioning army.

Actual

Confederates would consider the identification of camp slaves with Confederate

soldiers puzzling. In fact the idea put forth by many present Neo-Confederate that

the Confederate Army consisted of entire regiments of black soldiers is

contradicted by the fact that the Confederacy forbid the participation of black

soldiers in the army. Some point to the existence of the black Louisiana Native

Guard as an example of a Confederate regiment within the Confederacy but their

usefulness to the defense of New Orleans proved limited as the state militia

limited membership to “free white males capable of bearing arms,” and many of

the Native Guard became members of General Butler’s U.S. Corps d’ Afrique.(45) In spite of the fact that free blacks

volunteered service the response of the southern Government was a denial of any

role in combat for all blacks. In response to reports in Northern newspapers

that the Confederacy recruited blacks to serve, John B. Jones of the

Confederate War Department responded in his diary saying, “This is utterly

untrue. We have no armed slaves to fight for us, nor do we fear a servile

insurrection.” Much of Jones’ insistence was a response to the Emancipation

Proclamation and the Union policy of arming blacks, which he viewed as an attempt

to instigate a slave rebellion. (46) Viewing slavery and white supremacy as a

bedrock principle of Southern society and culture the very idea of arming

blacks undercut the reason for an independent South.

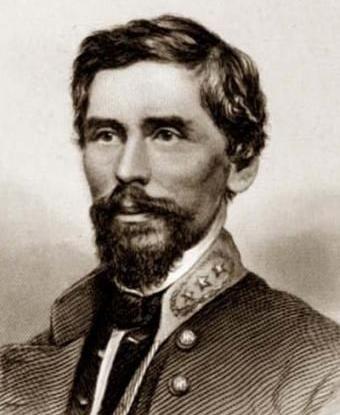

One of

the few lone voices calling for arming slaves was the Irish Confederate

general, Patrick Cleburne. By 1864, Cleburne believed that the reserves of

available white soldiers was exhausted and promoted the idea of offering

freedom to slaves who fought with the South. He also believed that the

participation of black soldiers in the army would, “strip the enemy of foreign

sympathy and assistance.” (58) But

Cleburne’s suggestion faced instant rejection as Joseph E. Johnson refused to

forward Cleburne’s proposal. It was not until January 1865 that faced with

defeat would Southern politicians consider the idea of a regiment of blacks.

But this plan of desperation was too little and too late as the Confederate government

fled Richmond.

|

| General Patrick Cleburne from National Park Service |

By

the end of the 19th century, southerners looked for ways to

understand and explain their defeat which led to the myth of the Lost Cause.

The Lost Cause viewed the War as not about slavery, but as a struggle for state’s

rights and a fight to protect the southern way of life. Central to the myth was

the benevolence of slavery and the loyalty of slaves. The participation of the

camp slaves became evidence of the loyalty and fealty of slaves to their

masters. During reunions of Confederate veterans, many former camp slaves

participated and became symbols of the loyal slave. As the civil rights

movement began to impact the South in the sixties and seventies, many groups

such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Daughters of the Confederacy

pointed to the camp slaves as evidence that the War was not caused by slavery

and that the Confederate cause had a just foundation. Kevin Levin provides an

excellent resource in refuting the myth of the black Confederate and another

essential reading in the role of African Americans in the American Civil War.

see:

|

| Photo of Sergeant Andrew M Chandler of the 44th Mississippi Infantry Regiment with his family slave Silas. This photo is often seen as evidence regarding the existence of black Confederates. But Silas served only as a camp slave and the weapons were most likely props. (see Levin, p. 13) |

No comments:

Post a Comment