The

Pilgrimage of Grace was a large popular uprising in Northern England which rose

in response to the religious and economic policies of Henry VIII.[1] The

dissolution of the monasteries led to the worst uprising during the reign of

Henry. The rebellion began at Louth in Lincolnshire in early October 1536. While the Lincolnshire

rebellion lasted only a fortnight the rebellion spread to Yorkshire. With an

army of over 30,000 the pilgrimage posed a serious threat to a kingdom lacking

a standing army. Many accept that

religious differences were a chief cause

of the Pilgrimage. The position of Roman Catholicism in North England remained

robust, while Protestantism found an unsympathetic audience. The seizure of the

monasteries by royal order stirred many of the commoners to action as

monasteries endured as centers of devotion. Pilgrim’s anger over the closings

led to rage toward authorities associated with the dissolution of the worship

centers which they so richly treasured.[2]

The most divisive religious issue was the Royal supremacy which declared Henry the

head of the English church. While many Northerners forcefully rejected the Act

of Supremacy, others reluctantly and narrowingly accepted the Act. The variety

of motives regarding the royal supremacy within the rebels reveals itself by

the absence of the Act in many of the lists and platforms early in the

Pilgrimage.[3]

|

| Portrait of Henry VIII by Han Holbein from Wikipedia |

But religion was not the

only motive for the rebels. While religious symbols and slogans shined brightly

during the Pilgrimage, economics was also

a prime motive for the rebellion. Chief among the economic concerns was the

practice of heavy taxation especially, during peacetime. Many believed that the

practice of oppressive taxation during peace was not only burdensome but

unconstitutional as well. Taxation was expected for the defense of the nation

but was highly detestable when there was no danger from war or invasion. The

unpopularity of taxes granted in 1534 which made no allowance for poverty spread

through all social classes. The 1536 Statute of Uses closed the loophole which

both nobility and gentry evaded feudal payments.[4]

Complaints about the Statute of Uses was

one of the first grievances set forth from

the Lincolnshire gentry.[5]

These same concerns attracted lawyers such as Robert Aske, who was instrumental

in the Pilgrimage leadership. Aske is a good example of a pilgrim holding both

religious and financial motives for his protest. He demonstrates his religious

devotion in his composition, The Oath of the Honourable Men saying, “Ye shall

not enter into this our Pilgrimage of Grace for the commonwealth, but only for

the love that ye do bear unto almighty God, his faith, and to holy church

militant.”[6]

But Aske also reveals his economic concerns in his account of his meeting with

nobles and gentry at Pontefract,

And that now the

profites of abbeys suppressed, tenths and

furst frutes,

went out of those partes. By occasion wherof, within short space or [of] yeres, there should be no money nor tresor in thos

partes, nether

the tenant to have to pay his rentes to the lord, nor the lord to have money to

do the King service with all.[7]

Aske

believed that once funds were exhausted from the dissolution of the abbeys and

monasteries that the property of the nobles and gentry would be the next

target. Also the North faced the prospect

of a failed harvest in 1535 which impacted both gentry and commoners. In

combination with taxes, the North faced burdensome economic conditions.

|

| Robert Aske in Yorke from Spartacus Educational |

The Subsidy Act of 1534 was

groundbreaking since it justified taxation in peacetime because of the “civil

benefits conferred on the realm by the king’s government.”[8]

The justification for taxation takes a new direction with the subsidy as taxes exist

not just for the common defense but also for the privilege of residing in the

kingdom.

The clergy also faced onerous

taxation. Many viewed clerical taxation as part of Henry’s assaults on the

church. The Valor Ecclesiasticus

taxed the clergy for ten percent of the “value of clerical benefices.”[9] On

the reverse, many also complained about forced tithes. Some such as the

Cumberland protesters believed that tithes should be voluntary. This proposal

brought conflict between laymen and

priests, with many priests viewing the idea

as another attack on the church. Further disagreement arose over the economic

policies of the Pope. Even within the Pilgrimage, there were those who

expressed resentment toward Rome because of the ecclesiastical

seizure of resources. These rebels did not envision a return to an arrangement

that allowed the Catholic Church with the ability to receive riches from the

English sees.[10]

In addition to real taxes and

levies, the rumor of taxes became just as convincing for many Northern rebels. Taxes

on livestock, acreage, and even on ecclesiastical church functions such as

baptisms, marriages, and burials became widespread gossip. One rumor even

claimed that a tax would yield a third of all a man owned. These rumors often

alarmed the poor with claims that peasants faced stiff taxation.[11]

Even the religious motivations of

the pilgrims contained a mixture of economic concerns. Many objected to the

closure of the monasteries and abbeys for purely spiritual motives, but others

saw the religious centers as economic centers of employment for peasants but

also as centers of charity. The monasteries cared for the poor during times of

need and want, while the king offered no charitable alternative. When defending

the monasteries Robert Aske not only provided spiritual reasons for their

maintenance, but included reasons such as alms-giving, hospitality, and

education.[12]

The monasteries were an economic engine for many people and provided many

functions for society. The rebels not only saw a religious vacuum with the

absence of the monasteries but the disappearance of economic opportunity.

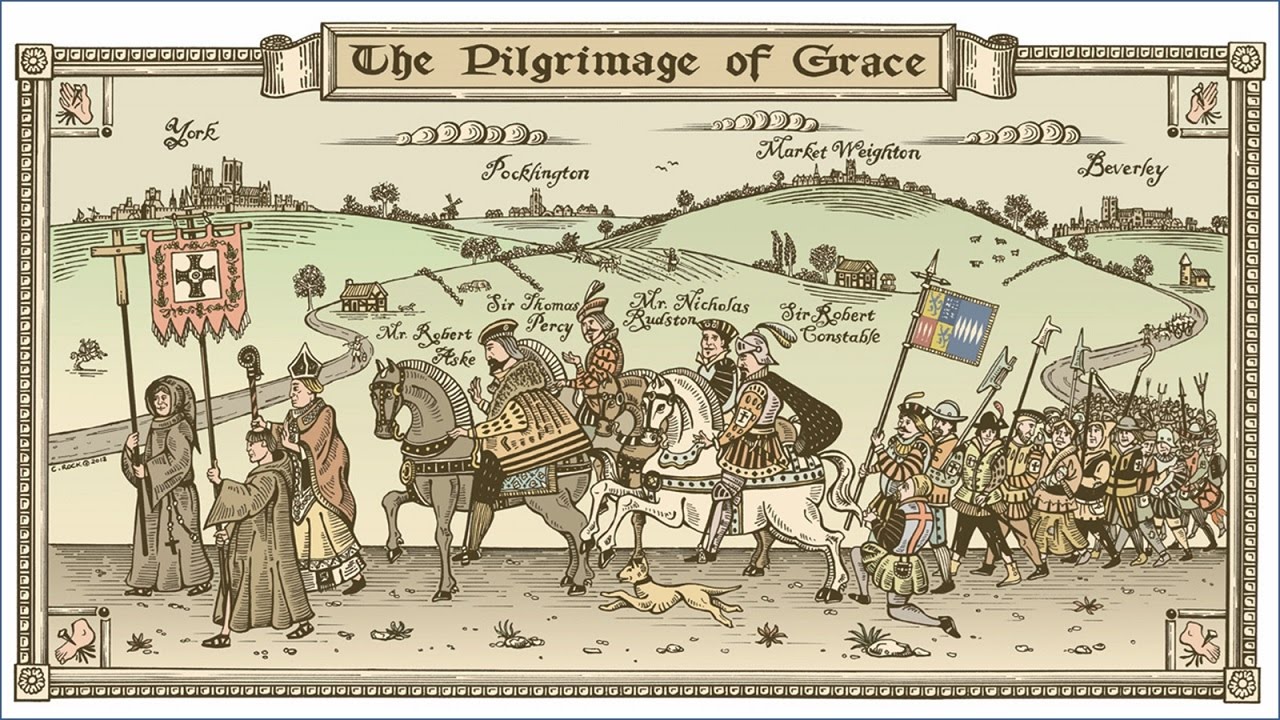

|

| Pilgrimage of Grace from Wikipedia |

The settlement at Doncaster also reveals the

economic concerns of the rebels. Many assumed that there would be a halt on the

payment of disputed taxes until a parliament would meet in York. Many

questioned Aske on the reliability of the supposed moratorium since the clerical

subsidy or “tenths be gathered.”[13]

Aske avoided the question, but the results were clear. The King still intended

to collect all taxes.

But for many pilgrims their concern

was philosophical. They asserted that Henry’s kingdom did not function as a Christian

commonwealth. Many blamed Henry’s ministers especially

Cromwell, while some laid the blame at the feet of the King. But they arrived

at these conclusions because they believed that a Christian kingdom dealt justly

with their subjects and that all citizens along with the king cooperated for

the mutual benefit of the realm. Unjust punishment and burdensome taxes did not

mirror the principles of a devout Christian kingdom. A Christian society was a rightly ordered society, and the Henrican

realm appeared broken in the eyes of many

pilgrims.[14]

|

Banner of the Holy Wounds, used during the Pilgrimage of Grace. An English counter-revolution in 1536 against schism from the Catholic Church and against the destruction of the monasteries from Wikipedia |

Facing a fatal danger to his rule,

Henry utilized diplomacy and negotiation through the Duke of Norfolk. The

rebels’ only motive was to see the return of monastic lands and a discussion of

their concerns within Parliament. The combination of seizure of the monasteries

with the practice of high taxation caused many in the north to place most of

the blame upon the King’s ministers especially Thomas Cromwell. The vast

majority of those involved in the pilgrimage refused to place blame upon Henry.

The King granted conceded to all of the

rebels demands and the uprising dispersed but soon afterward Henry soon broke

his word and declared martial law. Rebel leaders faced trial and up to 200

including Aske were executed.

|

| Clifford's Tower, the scene of Aske's execution in 1537 from Wikipedia |

The Pilgrimage of Grace was one of

the largest popular uprisings in English history. The rebels possessed a force

large enough to capture London if they desired. But their failure points to the

contradictions within the pilgrims. There was never a clear agreement on the

goals and purposes of the Pilgrimage. The inability for the rebels to

demonstrate their goals reveals that even “the traditionalist Catholic

population was severely divided.[15]

Bibliography

Fletcher,

Anthony, and Diarmaid MacCulloch. Tudor

Rebellions. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman, 1968.

MacCulloch,

Diarmaid. Thomas Cromwell: A

Revolutionary Life. New York: Viking, 2018.

Shagan, Ethan H.

Popular Politics and the English

Reformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003

[1] Ethan H. Shagan, Popular Politics and the English

Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003),

89.

[2] Shagan, 99.

[3] Shagan. 101-102.

[4] Shagan, 106.

[5] Anthony Fletcher and Diarmaid

MacCulloch, Tudor Rebellions (Harlow,

England: Pearson Longman, 1968), 48.

[6] Fletcher and MacCulloch, 143.

[8] Fletcher and MacCulloch,39.

[9] Shagan, 106.

[10] Shagan, 103.

[12] Shagan, 100.

[13] Shagan, 116.

[14] Shagan, 91.

No comments:

Post a Comment