|

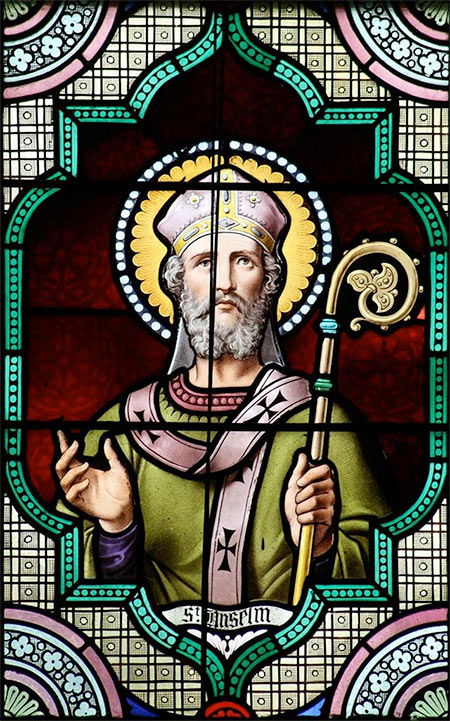

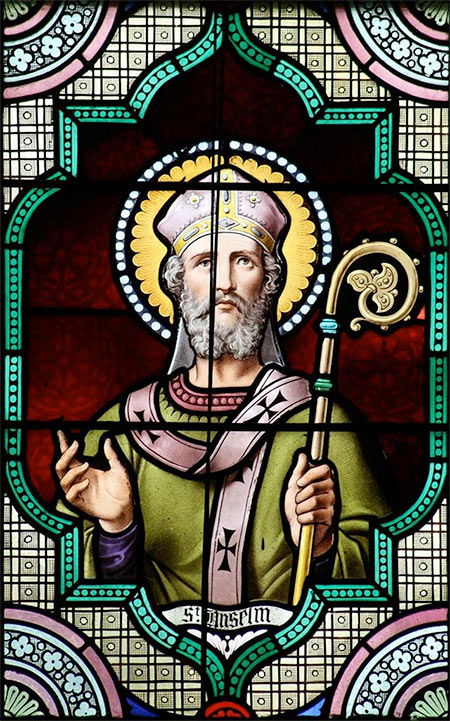

| Saint Anselm from History Today |

Anselm was a Benedictine monk, who rose to become the influential Archbishop of Canterbury. His ontological proof for the existence of God is still studied by philosophers and Christian apologists. He stands as one of the most important thinkers of the medieval period and his theological work

Cur Deus Homo or

Why God Became Man still impacts both Roman Catholic and

Protestant theology.

At the center of Christian theology lies

the person of Jesus Christ. Jesus’ death and suffering upon the cross remain the act which most Christians look upon

as central to their salvation. From the beginning of the Christian Church,

theologians debated the meaning of the death of Jesus upon the cross. Today,

most Catholics and Protestants hold to some form of vicarious atonement, teaching

that the death and suffering of Jesus upon the cross satisfied the Holiness and

Justice of God. The growth and widespread acceptance of plenary atonement

largely rest on the teaching of Anselm of

Canterbury in his work, Cur Deus Homo (Why God Became Man). The influence of

Anselm in framing this central doctrine of faith and his work merits an investigation into the formulation what

Christians believe about the Cross of Christ. This paper will explore Anselm

and his ideas of atonement through Cur Deus Homo and the impact upon the

Church.

Anselm was born

in 1033 in the town of Aosta within the Piedmont region of Italy. Knowledge

regarding the life of Anselm comes from a variety of sources including his

works and that of his close associate Eadmer. Eadmer first met Anselm briefly about

1079, and then thirteen years later he became the constant companion and

biographer of Anselm.

Eadmer possessed great skill as a biographer and his intimate relationship, and

careful listening allows the reader to grasp an understanding of the concerns

and personality of Anselm.

Eadmer’s account of Anselm’s final years remains

absent since Anslem ordered Eadmer to destroy the writings. Eadmer obeyed but

not before making a copy of his work.

Much of the knowledge regarding Anselm’s later life comes from his sermons and

letters.

|

| Eadmer from Wikipedia |

Anselm left his

Italian home in 1056 from what appears to be a contentious relationship with

his father. As a child, Anselm had a devoted relationship with his mother, but

her early death left him with a father with whom he had little in common.

He crossed the Alps and at the age of twenty-six became a Benedictine monk at

the abbey of Bec in Normandy. Anselm found himself drawn to Bec largely because

of the reputation of one of the priors of Bec, Lafranc.

He became Lafranc’s pupil and eventually

succeeded his master in the office of prior and then abbot. In 1093, Anselm

followed Lafranc as the Archbishop of Canterbury, an office he held until his death in 1109. Anselm was a reluctant

archbishop since his first love was study and reflection and he feared that the

duties of office meant time away from his study. He often found his administrative

duties onerous and longed for a solitary life of research and reflection, but

his superiors ignored his pleas and continued to place him in pastoral and

supervisory roles. Eadmer summarizes Anselm’s devotion to study,

For he had so much faith in the Holy Scriptures, that he firmly and

inviolably believed that there was nothing in them which deviated in any way

from the path of solid truth. Hence he applied his whole mid to that end, that

according to his faith he might be found worthy to see with the eye of reason these things in the Holy Scriptures

which, as he felt, lay hidden in a deep

obscurity.

Upon accession as the archbishop of Canterbury,

Anselm found himself in conflict with the monarchs of England. First with

William Rufus and then with Henry I over the question of investiture and the

relationship of the church and state in England.

Conflict with the monarchy sent Anselm into two exiles but reconciliation brought

him back to Canterbury, and he remained in office until his death in 1109.

Anselm was an active writer and wrote Cur Deus Homo while archbishop. Through

his writings, Anselm became one of the most important intellectuals of medieval

Europe and still impacts both contemporary Catholic and Protestant theology.

Anselm is

considered by many as the Father of scholasticism. Like the majority of

medieval theologians, Anselm fell under the influence of Augustine. The extent

of Augustine’s influence is difficult to determine but Anselm was never content

with a repetition of the Augustine. Anselm’s language rose from the theology of

Augustine, but his ideas and direction are his own.

Anselm saw no separation between faith and reason, but believed that there was

an indispensable unity between both. He held that this gave the theologian the

freedom to explore dogma using the “instruments of grammar and logic.

Anselm believed that reason aided the Christian in a fuller understanding of

the faith and theology and revealed the inner consistency and rationality of

Christian faith. The use of reason alone

verifies the logic of faith and Scripture, therefore the theologian can

deliberate on the nature of God without Scripture. Most of Anselm’s writings

contain little exegesis since he believed that he could reach truth through the

use of reason and logic.

Certain brethren have often and earnestly entreated me to put in

writing some thoughts that I had offered them in familiar conversation,

regarding meditation on the Being of God, and on

some other topics connected with this subject, under the form of a meditation

on these themes. It is in accordance with their

wish, rather than with my ability, that they have prescribed such a form for

the writing of this meditation; in order that nothing in Scripture should be

urged on the authority of Scripture itself, but that whatever the conclusion of

independent investigation should declare to be true, should, in an unadorned

style, with common proofs and with a simple argument, be briefly enforced by

the cogency of reason, and plainly expounded in the light of truth. It

was their wish also, that I should not disdain

to meet such simple and almost foolish objections as occur to me.

The importance

of reason for Anselm cannot be understated and places him first among a long

list of medieval scholastics. He believed that logic was an essential tool for

the theologian but he did not drive a wedge between logic and faith. Reason

does not supplant faith but reason places one on the path towards true faith. A

conclusion might appear sound but if it contradicts the teaching of Scripture

then this is a sign that one needs to rethink the soundness of the argument.

Humanity cannot comprehend the full mystery of the Godhead but God is rational

and any communication from God is coherent and without contradiction. Since

Scripture is the primary source of revelation then it contains no contradiction

with reason. Reason is at the forefront of Anselm’s classic works the Monologion

and the Proslogion. Within the Monologion Anselm sought to

explore the divine attributes of God and his existence through the use of

reason. Anselm claims that since there are many signs and kinds of good then

there must be a supreme good through which all unite. Because one can discern different levels of goodness leads

to the conclusion that there exists absolute goodness. Therefore, Anselm

reasons that there is one “being greater

and higher than all others through whom they all exist.”

In the Proslogion, Anselm argues for his ontological proof for God’s

existence in which he claims that God is that, “whom nothing greater can be thought.

Because God is a being which nothing greater can be thought then he must exist not only in one’s mind but also in

reality. The ontological argument

of Anselm remains a key argument within apologetic debates regarding proofs of

the existence for God. The original title of the Proslogion, Fides quaerens intellectum

or Faith seeking understanding point to the importance of reason for Anselm.

The correct use of reason points to God, therefore Anselm attempts to

understand a faith he already believes.

Anselm’s

theological masterpiece remains Cur Deus Homo. and like the theologians

of the ancient church. Anslem strives to understand why God lowered himself by

becoming a man and subjecting himself to the humiliating death upon the cross.

Most theologians of the early church debated the nature of God and the humanity

and divinity of Christ. The work of the atonement and soteriology was not a debate during this period. The idea of

atonement is central to understanding Anselm and other theologians who grapple

with the meaning of the cross of Christ. Atonement entails the proposition that

sinful humanity needs redemption from sin and that the cross is a means of

salvation. When exploring the question of the atonement one must ask how Christ

through the cross brings reconciliation

between God and humanity. The meaning and

work of Christ upon the cross continues to stem debate and theological

discussion among the Christian world. Ancient

theologians proposed a number of theories

many often appearing contradictory with some ideas being held by the same theologian.

Early Christians understood that Christ brought salvation but few asked the

question how Christ saved. Theologians who allowed no compromise regarding

”trinitarian and Christological orthodoxy were quite willing to manipulate

soteriological theories and images

without similar compunction.”

Irenaeus connected

the incarnation to salvation by proclaiming that Jesus’s incarnation provided

redemption. He believed that “human nature was sanctified, transformed, and

elevated by the very act of Christ’s becoming a man.”

Jesus’ very appearance as a man demonstrated Christ’s ability to save fallen

humanity. Irenaeus’ emphasis on the Incarnation was a response to what he

viewed as Gnostic heresy which deemphasized the importance of the Incarnation.

The divine Son of God became the Son of Man to accomplish redemption.

But God the Father was very merciful: He sent His creative Word, who in coming to deliver us came to the very place

and spot in which we had lost life, and

brake the bonds of our fetters. And His light appeared and made the darkness of

the prison disappear, and hallowed our birth and destroyed death, loosing those same fetters in which we were enchained. And He manifested |the

resurrection, Himself becoming the first-begotten of the dead, and in Himself

raising up man that was fallen, lifting

him up far above the heaven to the right

hand of the glory of the Father.

Irenaeus’ viewed that the relationship lost through

the first man became renewable through Christ. Irenaeus used the term

recapitulation to describe that humanity “fell in our solidarity with the first

man, we can be restored through our

solidarity with Christ.”

|

| Irenaeus from Wikipedia |

Many ancient

theologians held to a theory often called the Ransom Theory. They maintained that

humanity belonged to Satan and that God offered Jesus as a ransom or sacrifice

for sinners. The devil looking at the

agreement as a bargain because he viewed Christ as a far greater prize. But

once Christ arrived in hell, Satan lacked the power to hold him, and Christ

entered into mortal combat for the salvation of humanity. While the crucifixion

appeared as a defeat, Christ resurrected

in triumph and broke the power of the enemy and his victory made immortality

possible for believers.

They believed that in the ransom, Christ defeated the forces of evil. Irenaeus,

Origen, and Gregory of Nyssa taught versions of this theory. Origen is very explicit in his use of the word

ransom and insists that the ransom which

Christ paid was meant not for God but for

the Devil. Gregory of Nyssa expounds on the ransom in Chapter 23 of the Catechetical Oration,

The Enemy, therefore, beholding in Him such power, saw also in Him an

opportunity for an advance, in the exchange, upon the value of what he held. For this reason he chooses Him as a ransom for

those who were shut up in the prison of death. But it was out of his power to

look on the unclouded aspect of God; he must see in Him some portion of that fleshly

nature which through sin he had so long held in bondage…His choosing to save

man is a testimony of his goodness; His making the redemption of the captive a

matter of exchange exhibits His justice, while the invention whereby He

enabled the Enemy to apprehend that of which he was before incapable, is a

manifestation of supreme wisdom.

Athanasius holds to a doctrine of atonement

similar to other ancient fathers with some distinctions.

He held that by physically becoming a man,

Christ repaired the image of God humanity lost due to the corruption of sin.

We have seen that to change the corruptible to

incorruption was proper to none other than the Savior Himself, Who in the

beginning made all things out of nothing; that only the Image of the Father could

re-create the likeness of the Image in men, that none save our Lord Jesus

Christ could give to mortals immortality, and that only the Word Who orders all

things and is alone the Father's true and sole-begotten Son could teach men

about Him and abolish the worship of idols.

The restoration of the image of God within man

allows all men to recover the true knowledge of God and then enjoy full

fellowship with God.

Athanasius’ major concern was the battle against Arian heresy, the nature of the atonement and redemption was not

his primary concern. Like other ancient theologians, he felt the urgency to

defend Nicean Christianity against Arianism which limited the full divinity of

Christ.

|

| Athanasius from Wikipedia |

Augustine

also stresses the Incarnation of Christ as the instrument of man’s salvation

and stresses Christ’s role as mediator between God and humanity. The image of

God in man remains but it has been greatly damaged. Augustine pictures Christ

as the physician who brings healing through the love and grace of God.

Augustine also makes reference to mankind

trapped in the bondage of Satan and the need of the redemption of Christ to

release sinners. Augustine recognizes no proprietary rights of the devil over

humanity, but he still describes humanity “delivered into the power of the

devil.”.

He sees the passion and the Resurrection as Christ’s victory over Satan and

through the mediation of Jesus, the Devil lays defeated by the righteousness of

Christ.

Augustine emphasizes the righteousness of Christ saying,

But the devil was to be overcome, not by the power of God, but by His righteousness. For what is more powerful than the

Omnipotent? Or what creature is there of which the power can be compared to the power of the Creator?

While different than earlier Church Fathers,

Augustine still bears similarity to the Ransom Theory held by Origen and

Gregory of Nyssa nonetheless Augustine emphasizes how sin allows Satan a hold

on the life of the believer but that hold loses power through the sacrifice

offered by Christ in His passion.

While

Anselm’s apologetic works appear primarily as works of philosophy, Cur Deus

Homo is chiefly a work of theology. Nevertheless, Anselm utilizes the same

philosophical method of reason in his examination

of the Atonement. Anselm explains in his preface that his goal is to explain with

reason the skeptic’s objections to the

Christians faith and by “equally clear reasoning and truth that God created

humanity to enjoy eternal life.

But to demonstrate this to the unbeliever, Anselm recognizes the need to show

that mankind needed the intervention of a

“Man-God” to deliver salvation.

Anselm

began the writing of Cur Deus Homo

between 1095 and 1098 and completed it during his exile in Capua. Eadmer

describes Anselm’s period in Capua as a period of study and reflection similar

to his early life before he became an abbot. Eadmer credit’s prayerful

reflection and love of God as giving Anselm the motivation for writing the

book.

Most of Cur Deus Homo takes the form of a dialogue between Anselm and

Boso, one of his monks from Bec. Boso serves the function of a advocatus diaboli

or devil’s advocate and brings challenges to Christian doctrine which Anselm

seeks to respond.

It’s possible that much of his motivation for writing

rose from concerns over the

questions posed by Jews and Muslims. During 1092, questions arose regarding the

incarnation from questions raised by some learned Jews in London

and during his exile in Capua, Anselm had some

positive encounters with Arabs during the siege of Capua.

His apologetic concerns perhaps lay behind his

motive for writing Cur Deus Homo.

The

first question Anselm answers is the necessity of the Incarnation. Because God

is omnipotent then one might conclude that He could redeem man through an angel or another person or just through his

command. According to Anselm, God’s actions are not due to any external

compulsion or inability. The Incarnation of Christ is not a decision God makes

because of any outside force but is a result of God’s nature and completely

free choice. Anslem wishes to answer

the objection that the Incarnation demeans God by lowering Him as a suffering

human. Anselm argues that the incarnation is vital for the redemption of mankind.

Because Adam fell into sin, Anselm explains that only a sinless God-man could

bring the necessary satisfaction for the sin of humanity.

For it was appropriate that, just as death entered the human race

through a man’s disobedience, so life should be

restored through a man’s obedience; and that, just as the sin which was

the cause of our damnation originated from a woman, similarly the originator of

our justification and salvation should be born of woman.

Anselm deals with the confusion that many

unbelievers have about the Incarnation declaring that they lack an

understanding of Christianity.

People who say this do not understand what we believe. For we affirm

that the divine nature is undoubtedly

incapable of suffering, and cannot in any sense be brought low from its exalted

standing, and cannot labour with

difficulty over what it wishes to do. But

we say that the Lord Jesus Christ is true God and true man, one person in two

natures in one person. In view of this,

when we say that God is suffering some humiliation or weakness, we do not

understand this in terms of the weakness

of the human substance which he was taking upon himself… For we are not, in

this way, implying lowliness on the part on the part of the divine substance,

but are making plain the existence of a single person comprising God and man.

Anselm

regards the dilemma of humanity to be a problem of a broken relationship. He

regards sin as a debt owed to God whose nature demands satisfaction from a holy

and righteous God. In Adam, all humanity fell into a sinful condition. Sin placed mankind

into a predicament that they could not solve for themselves. Anselm contended that humanity owed a debt to God not

to Satan because God’s honor and righteousness remain

dishonored. Sin is to take from God the worship and adoration due to him alone.

Anselm describes the debt,

This is the debt which an

angel, and likewise a man, owes to God. No one sins through paying it, and

everyone who does not pay it, sins. This

is righteousness or uprightness of the will. It makes individuals righteous or

upright in their heart, that is, their will. This

is the sole honour, the complete honour, which we owe to God and which God

demands from us… Therefore, everyone who sins is under an obligation to repay

to God the honour which he has violently

taken from him, and this is the satisfaction which every sinner is obliged to

give to God.

Anselm believes that forgiveness without atonement and

satisfaction is impossible because forgiveness without satisfaction offends the

nature of God. Sin must receive punishment as the holiness of God demands

justice for the debt of sin. Anselm insists that,

it is not fitting for God to

forgive a sin without punishment…. If a sin is

forgiven without punishment: that the position of sinner and non-sinner

before God will be similar-and this does not befit

God.

Anselm stresses the

justice of God, which demands satisfaction and cannot forgive by mere fiat

since forgiveness without the payment of debt is a violation of the “order in

the universe that God had to uphold to be consistent with himself and with his

justice.”

Anselm refutes the ransom theory, held by so many

theologians of the ancient church. He states that God cannot simply

“raise anyone who is to any extent bound by indebtedness arising from sin.”

The one who claims that God can simply

overlook or proclaim sin forgiven without satisfaction underestimate the great

burden of sin. Anselm admits that Satan possesses

power over sinful humanity but the debt of man remains a debt owed to God not

Satan. Sinners who allow themselves captivated

by Satan offend God. If the payment of sin belonged to Satan, then Anselm

maintains that the need of the Incarnation was unnecessary. The problem with

the ransom theory is that it fails to account for the necessity of the Incarnation and the need for the sacrifice of Christ to

obtain forgiveness.

The

ransom theory also fails the test of justice. The ransom theory claims that

Satan possessed rights over sinful humanity and God must respect those rights.

The life and death of Christ was an opportunity for God to play on the devil’s

greed by giving him a deal he could neither reject or win because of the power

of Christ. Losing the bet caused Satan to lose his sovereignty over mankind.

Anselm rejects this picture of justice.

For, supposing that the devil, or man, were his own

master, or belonged to someone other than God, then perhaps one could justly

speak in those terms. However, given that neither the devil nor man belongs to

anyone but God, and that neither stands outside God’s power.

The ransom theory fails the test

of justice because the devil has no dominion over humanity, for he is subject

to the judgment and sovereignty of God. Satan, like humanity, is a creature

subject to the God’s sovereign rule. And redemption is solely under God’s

providential will. If Satan has any involvement on the suffering of humanity

then it is not a decision of the devil but the judgment of God who uses even

evil things to accomplish his purposes.

Once establishing the impasse which sin causes for humanity, Anselm turns

to the solution offered by Christ in Book II. Anselm asserts that salvation

depends upon payment for the debt of sin,

If, therefore, as is agreed, it is necessary that the

heavenly city should have its full complement made up of members of the human

race, and this cannot be the case if the recompense of which we have spoken is

not paid, which no one can pay except God, and no one ought to pay except man;

it is necessary that a God-Man should pay it.

God remains determined to redeem

the human race from the consequences of their sin. Humanity remains the

pinnacle of His creation and His intervention is vital to the preservation of

the human race. God’s purpose is the completion and perfection of His creation.

Because sin came into the world through the first human then justice required

recompense from a human. But no one has the ability to stand guiltless before

the justice of God because all remain tainted by sin. Only Jesus fit the needed

requirements of justice since Jesus Christ is fully man and God. Anselm affirms

the creed laid out by the Council of Chalcedon by affirming that Christ is one person

with both human and divine natures. Anselm concludes that salvation is

“necessary for divine and human nature to combine in one person.”

The justice of God receives

satisfaction from the death of Christ which “outweighs the number and magnitude

of all sins.”

Even small sins are of “such infinite magnitude” that they offend the holiness

and justice of God. Christ’s atonement is so potent that His death redeems the

sins of those who put him to death. According to Anselm, logic dictates that the

Heavenly city have citizens from the human race which is impossible unless

sinners receive forgiveness and remission of sins. Remission of sins only

comes,

through a man

who is identical with God and who by his death reconciles sinners to God. We

have already found Christ, whom we acknowledge to be God and man and to have

died for our sakes.

Boso

admits that Christ freely gave his life as a gift to pay recompense for the

sins of man but asks how his death pays for sin and the difference between the

death of Christ and those of John the Baptist and other martyrs. Anselm explains the uniqueness of Christ’s death

because Christ alone paid a “debt which he did not owe.”

Christ paid a debt which sinners were unable to pay and his willingness to lay

his life revealed an act of undeserving grace. Christ was under no obligation

to save humanity, it was his “prerogative to suffer or not to suffer.” Jesus’

death was not the result of a debt to the Father or humanity rather he died

because of a free desire to save mankind. Christ was free not to die but his

willingness to die renders his sacrifice all the more magnificent.

Because Christ freely and willingly gave his life then Anselm reasons

that the Son deserves recompense for his sacrifice. The reward owed to Jesus is

a gift the Son gives to those lack any ability to pay their debt. The salvation

of the human race is the first fruits and reward for those He died upon the

cross. On whom id it more appropriate for him to bestow the reward and recompense for his death than on

those whose salvation, as the logic of truth teaches us, he made himself a man,

and for whom, as we have said, he set an example, by his death, of dying for the

sake of righteousness? For they will be imitators

of him in vain, if they are not sharers in his reward.

Anselm makes it clear that the debt of sin was owed

to God. There was no need inherent within God that required the death of Christ

rather it was a sacrifice freely given. Anselm clearly refutes the ransom

theology held by the early church. Mankind did not owe the devil a debt for

humanity’s sin offended God.

Certainly God did not owe the devil anything but punishment, nor did

man owe him anything but retribution-to defeat in return him by whom he had

been defeated. But, whatever was demanded from man, his debt was to God, not to

the devil.

The

atonement of Christ reveals both the mercy and justice of God. The great sin of

humanity and the demands of God’s justice appear insurmountable when first

observed but God’s mercy appears through the self-sacrifice of the Son of God

who freely offered himself up for the sinful debt humanity accumulated. Redemption

occurs because the atonement of Christ offers sufficient satisfaction for the debt of sin owed by the human race.

If

sin is forgiven without punishment or satisfaction then the forgiveness is

cheap and without meaning. This places sinful humanity and sinless humanity in

the same standing. The holiness and justice of God demands punishment and the

state of sin remains. Injustice stands above the law and holiness with

unpunished sin. Justice demands

punishment but Anselm recognizes that the intervention of God through the

passion of Christ demonstrates the mercy of God. The death of Christ is

sufficient for any sin and nothing could be more merciful than the sacrifice of

the Son upon the cross.

Some

scholars maintain that the roots of Anselm’s atonement theology lay in the practice of German law

and that the idea that sin must receive either punishment or satisfaction was a

new idea imported from feudal law practices.

But earlier Latin theologians discussed satisfaction in the context of penance

as a way satisfying the Lord. Penance appeared

to overlap but failed because, “

even in rendering such satisfaction, man was giving God only what he

owed him. But the satisfaction offered by the death of Christ possessed

infinite worth, and this the redemption on the cross could be seen as the one supreme

act of penitential satisfaction.

One

of the earliest critics of Anselm’s doctrines was the theologian Peter Abelard,

whose most active years as a theologian and philosopher followed the death of

Anselm. Abelard appears as the foremost opponent Anselm’s doctrine of the

atonement and the principal proponent of the exemplarist

or moral example theory.

Abelard’s moral influence theory is a subjective theory of the atonement

because it emphasizes how the moral example of the cross brings change in people.

Abelard also rejected the ransom theory of the atonement and asserted that the

devil had no rights over humanity but he also rejected the proposal that the

death of Christ brought satisfaction for sin.

How very cruel and unjust it seems that someone should require the

blood of an innocent person as a ransom, or that in any way it might please him

that an innocent person be slain, still less that God should have so accepted

the death of his Son that through it he was reconciled to the whole world. These and similar things seem to

us to inspire a not insignificant question, namely, concerning our redemption

and justification through the death of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Abelard rejected the idea that the death

of Christ satisfied the honor and justice of God rather the cross was the

ultimate display of God’s love. The importance of the atonement was the

impact the love of God had upon the hearts of

humanity.

Nevertheless it

seems to us that in this we are justified in the blood of Christ and reconciled

to God, that it was through this matchless grace shown to us that his Son

received our nature, and in that nature, teaching us both by word and by

example, persevered to the death and bound us to himself even more through

love, so that when we have been kindled by so great a benefit of divine grace,

true charity might fear to endure nothing

for his sake…Therefore, our redemption is that supreme love in us through the

Passion of Christ, which not only frees us from slavery to sin, but gains for

us the true liberty of the sons of God.

Abelard

asserts that salvation is the declaration of God’s love demonstrated in the

life and death of Jesus. The purpose of the atonement was to restore the love

of God into the hearts of humanity through the self-sacrificial

example of Christ. The was no need of reconciliation from God since he offered

forgiveness but man needs to turn his heart toward the forgiveness offered by

God. The purpose of the life and death of Jesus was to demonstrate the love of

God to a distant humanity. By faith, the Christian ascesses the transforming power of God

exhibited by the example of Jesus. Abelard presented his

views in a short passage in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans and was

not a full account of his beliefs on the atonement.

Abelard’s brief explanation of the

moral influence theory of the atonement finds renewed interest in contemporary

theology which decry the picture of an angry and wrathful God, who demands

justice. The moral example of Jesus and his sacrificial forgiveness

demonstrated in his passion serves as a moral exemplar and incentive for a

changed life. Anselm anticipates this criticism when Boso questions Anselm

regarding the mercy of God. Anselm exhibits that God’s mercy cannot conflict

with His law or the moral ordering of the universe. Any consideration of

God’s mercy and kindness must account also for God’s judgment. While Boso maintains that complete forgiveness appears consistent with a God of mercy, Anselm

counters that forgiveness is not just, if justice remains forgotten. God himself is both mercy

and justice and any doctrine which neglects both falls short according to the

logic presented by Anselm. God can neither abandon his creation nor can he

leave the debt of sin unpunished.

The debate between Anselm and

Abelard continues to frame the debate over the nature of the Atonement in

Christian theology. Anselm’s argument that the death of Christ satisfies the

justice of God remains the primary orthodox position within the Roman Catholic Church and most Protestant

Churches. The doctrine of the plenary substitutionary atonement held by many

Protestants bears great similarity and dependency upon Anselm’s explanation of

the death of Christ. Christ’s death is penal because he paid the judicial and

legal price for sin and it is substitutionary

because Christ was the substitute for sinners who deserved punishment. While

Anselm never spoke of a substitution the concept is similar to Christ

satisfying the justice of God. The influential Westminster Confession of Faith

summarizes the principle of substitution held by most Protestants,

Christ, by His

obedience and death, did fully discharge the debt of all those that are thus

justified, and did make a proper, real, and full satisfaction to His Father's

justice in their behalf. Yet, inasmuch as He was given by the Father for them, and His obedience and satisfaction accepted in

their stead, and both, freely, not for anything in them, their justification is

only of free grace; that both the exact justice and rich grace of God might be

glorified in the justification of sinners.

The

language of debt and justice is very similar to the words used by Anselm and

while the Westminster divines sought to justify their doctrine with Scripture

the progression of their doctrine of atonement clearly derives from the

doctrines first presented by Anselm.

Recent years interest in the ransom

theory has grown since the publication of ChristusVictor by Gustaf Aulen. While Aulen

rejects the idea of a ransom paid to Satan he proposes that the central purpose

of the atonement is the defeat of sin and the forces of evil to free humanity

from their captivity and oppression. Aulen

criticizes Anselm for holding to a view of that world which is at its heart

legal.

In this scheme Law is represented as the

granite foundation of the spiritual world. To the classic idea, on the other

hand, it is essential that the work of atonement which God accomplishes in

Christ reflects a Divine order which is wholly different from a legal order;

the Atonement is not accomplished by strict fulfillment the demands of justice,

but in spite of them. God is not, indeed,

unrighteous, but He transcends the order of justice.

Aulen maintains

that the Latin viewpoint of Anselm derives from the legalistic character of the

medieval worldview. He maintains that theologians of the Reformation then

accepted Anselm without questioning the legalism which lay beneath the

doctrine.

Aulen further rejects the subjective view of Abelard and many contemporary

theologians as still captive to individualism and rationalism. While liberal

Protestantism opposes the Scholasticism, Aulen

claims that the moral influence view of the atonement remains, “penetrated from

end to end by an idealistic philosophy, and seeks to interpret the Christian

faith in the light of a monistic and evolutionary worldview.”

According to Aulen, the Christus Victor

is the classical view of the atonement since variations of the view dominated

Christian doctrine for most of church history. The atonement is a victory over

sin death, and the devil. Sin is an objective power holding power over humanity

which the death and resurrection of Christ defeats. Salvation is the fruit of

the triumph of Jesus over evil.

The victory of

Christ over the powers of evil is an eternal victory, therefore present as well

as past. Therefore Justification and Atonement are really one and the same

thing; Justification is simply the Atonement brought into the present, so that

here and now the Blessing of God prevails over the Curse.

Aulen’s ideas continue to cause ripples

within theological circles and his points have reframed the deliberations over

atonement from a two-sided dispute into a three-sided

debate. Opponents of Aulen point to the fact that “Anselm views Christ’s

satisfying death within a larger framework of Christ’s entire saving work as

restoring human nature.” Under Anselm human nature receives exaltation and

glory as the special creation of God.

Christ exalts human nature through the

Incarnation and restores the relationship between God and man through the work

on the cross repairing and bring humanity into an exalted position. Aulen accuses Anselm of divorcing Incarnation

and Atonement but as seen earlier Anselm roots his doctrine of Atonement in

Chalcedonian doctrine and views the Incarnation and Atonement as an organic

whole.

The cross remains at the of Christianity

and the debates over the purpose and meaning behind the death of Christ

continue to rage within Christian circles since the beginnings of the early

church. The cross occupies both theological and artistic disputes within the

Christian and Western world. Anselm still looms large in any examination of the

atonement. While Scripture remains the tool used by most theologians, Anselm's use of reason and logic sets an

apologetic example of early Scholasticism. No theological or historical

examination of the impact of atonement is complete without a consideration of

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo.

Bibliography

Abelard, Peter. Commentary on the

Epistle to the Romans. Translated by Steven R. Cartwright. Washington: The

Catholic University of America Press, 2011.

Anselm. Anselm of Canterbury: The

Major Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Athanasius, On the Incarnation of

the Word, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, https://www.ccel.org/ccel/athanasius/incarnation.v.html

Augustine. On the Holy Trinity.

New Advent. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/130113.htm

Aulen, Gustaf. Christus Victor: An

Historical Study of the Three Main Types of the Idea of Atonement, translated

by A.G. Hebert, Austin: Wise Path Books, 2003.

Baldwin, Joseph W. The Scholastic

Culture of the Middle Ages, 1000-1300. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland

Press, 1971.

Bysted, Ane L. The Crusade

Indulgences: Spiritual Rewards and the

Theology of the Crusades, c. 1095-1216. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Davies, Brian and Brian Leftow, editors. The Cambridge Companion to Anselm. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2004.

Eadmer, The Life of St. Anselm: Archbishop of Canterbury, Translated

by R.W. Southern. , edited by R.W. Southern, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1962.

Fairweather, Eugene R, A Scholastic Miscellany: Anselm to Ockham, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970.

Grane, Leif. , Peter Abelard, Translated

by Frederick and Christine Crowley.New York: Harcourt, Brace and World,

Inc.1964.

Gregory of Nyssa. Catechetical

Oration, Christian Classics Ethereal Library,

https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf205.xi.ii.xxv.html

Hauser, Alan J. and Duane F. Watson, editors. A History of Biblical Interpretation, Vol. 2: The Medieval through the

Reformation Periods. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.,

2009.

Hopkins, Jasper. A Companion to

the Study of St. Anselm. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972

Irenaeus. The Proof of the

Apostolic Preaching, The Tertullian Project,

http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/irenaeus_02_proof.htm

Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian

Doctrines, New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1960.

Komonchak, Joseph A. “Redemptive Justice: An Interpretation of the Cur

Deus Homo,” The Dunwoodie Review,

12(1972) 33-55.

Lane, Tony. A Concise History of

Christian Thought. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2006.

Leftow, Brian. "Anselm on the Necessity of the Incarnation." Religious

Studies 31, no. 2 (June 1995): 167-85.

McBrian, Richard P. Catholicism.

Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1980.

McGiffert, Arthur Cushman. A

History of Christian Thought, Volume II: The West From Tertullian to Erasmus,

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933.

McIntyre, John. St. Anselm and His

Critics: A Re-Interpretation of the Cur Deus Homo, Edinburgh: Oliver and

Boyd, 1954.

Ortland, Gavin. “On the Throwing of Rocks: An Objection to Hasty and

Un-careful Criticisms of Anselm’s Doctrine of the Atonement,” The Saint Anselm Journal, 8 no.2 (Spring

2013), 1-17.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600).

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Growth of Medieval Theology (600-1300).

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Melody of

Theology: A Philosophical Dictionary. Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

1988.

Radford, Rosemary, Carter Heyward, and Mark L. Taylor. Contemporary Christologies: A Fortress

Introduction, Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2010.

Southern, R.W. Saint Anselm A Portrait in a Landscape. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Southern, R.W. Saint Anselm and

His Biographer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Welch, A.C. Anselm and His Work. New York: Charles

Scribner's Sons, 1901.