|

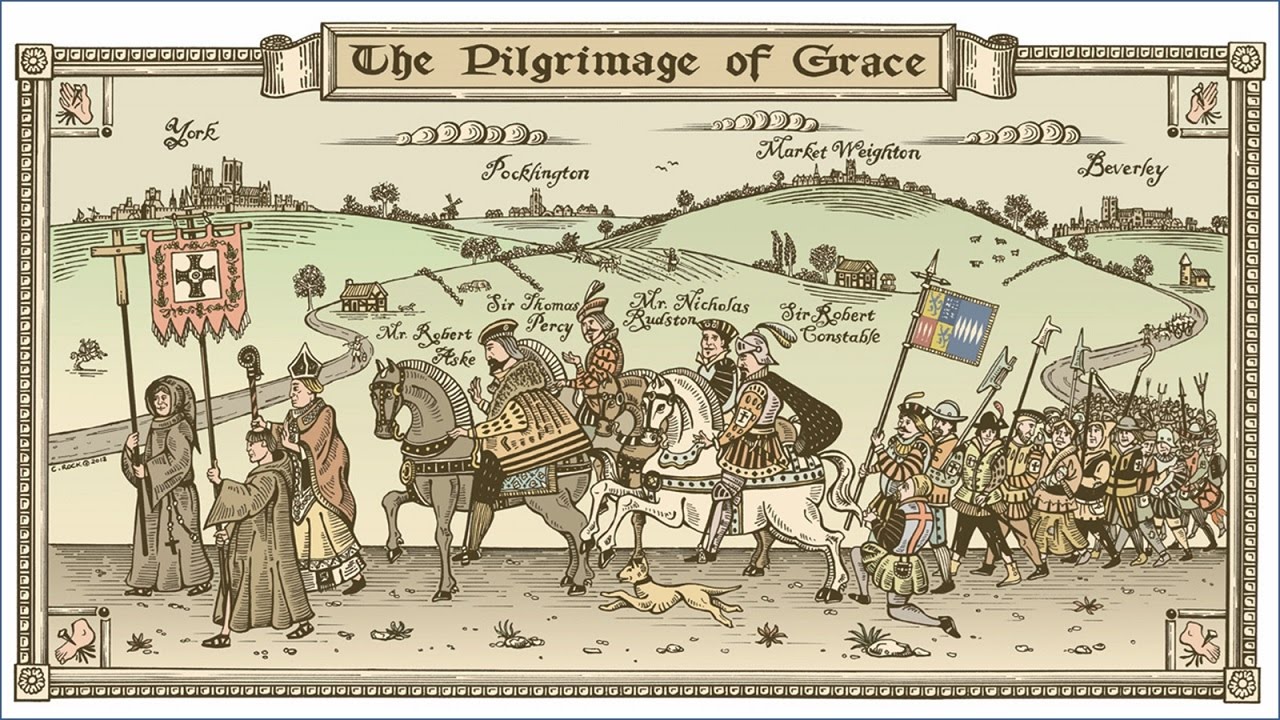

| Detail from The Suppression of the Taiping Rebellion, ink on silk. |

|

| Add caption |

Recent news from China shows a deep

suspicion from the Communist Chinese rulers for what they consider foreign religious

interference. Thousands if not over a million Muslims languish in internment camps in the western Xinjang region which the Chinese government claims are centers for voluntary education and training. As Christianity spreads throughout

China in recent years the reaction of the Chinese government has been to forcibly close churches and jail pastors. The forced closing of the Early Rain Covenant Church in the city of Chengdu, recently led to a nine-year prison sentence of the pastor Wang Yi. Much of the reaction and persecution of

religious groups stems from the totalitarian and authoritarian nature of the Chinese

Communist Party, but many answers also rise from a study of Chinese history. As

the Western world began to explore and colonize the Western hemisphere and develop

Asian trading posts, the Chinese Qing dynasty remained confident in their own

superiority. The Chinese rejected any interference from Western Europe and saw

no need for trade or use for Western products. Yet a number of events brought

China and Westerners into conflict and led to years of Chinese resentment.

By the mid Nineteenth century, China

confronted problems at many different levels. Contacts with Western countries

increased as Europeans and Americans clamored for increased trade with China.

While many westerners pursued trade opportunities, missionaries looked to

establish a Christian presence in China with converts among China’s millions. Profoundly

desiring isolation from Western influence, the Qing monarchy resisted Western

intrusion, but the British victory after the Opium Wars forced the presence of

European and American traders within China along with Christian missionaries

who worked to spread Christianity.[1]

Caught between a monarchy desperate to maintain control and foreigners eager

for riches or a spiritual kingdom was the common Chinese struggling to live out

their bare existence. Jonathan Spence in his book, God’s Chinese Son and Diana Preston in her book, The Boxer Rebellion describe two of the

most violent upheavals in Chinese history which demonstrate the ferocious

reaction of the frustrated millions against both Western influence and Qing

corruption.

|

| Hong Xiuquan |

Hong Xiuquan

was a lower-middle-class man of Hakka origin, whose dream to become part of the

Qing administration continually faced frustration as he failed to pass the

required Confucian examinations. A dream vision followed by his reception of a

Christian tract led Hong to understand himself as the younger brother of Jesus

with the mission to establish the Kingdom of God on earth. Unlike many messianic

figures, Hong gathered massive numbers of followers ready to obey and fight

against the demonic forces of the Qing monarchy. The appeal of his message to

so many reveals not only the ability of Hong to win converts but also the desperate

situation of many Chinese peasants. Hong not only shared a religious message

but provided a “promise of solidarity against threatening forces all around.[2]

Common Chinese trapped between oppressive forces reached out to the stabilizing

assurance offered by Hong and his vision of a Heavenly Kingdom. With the

promise of a place within the Heavenly Kingdom, millions followed Hong into a

revolution that consumed China and killed millions.

Diana Preston in her book, The Boxer Rebellion discusses a

revolutionary movement of Chinese people undergirded by the common people. Preston

presents a more popular interpretation of the Rebellion rather than an academic

account.[3]

The Boxers, like the followers of Hong, were a mystical peasant group

frustrated with conditions in China. They were “anti-Christian, antimissionary,

and antiforeign” and believed that through their exercises and magic formulas

that their mission was to free China of foreigners and Christianity.[4]

The Boxer movement swept rapidly through China which and was a “heartfelt

response to desperate and worsening conditions in northern China and an

increasing sense of impotence.[5]”

The Boxers gave their followers a sense of power against frustrating conditions

in a similar manner that the followers of Hong Xiuquan found their purpose in

the Taiping community. The Qing monarchy led by the Empress Dowager, Tzu

Hsi, attempted to utilize the Boxers for

her own purposes. While her influence over the Boxers appeared unclear, she

shared with them a hatred and fear of foreign influence. But the rise of the

Boxers was a movement born from peasants frustrated with economic and natural

disasters who blamed their misfortunes on “foreign interference and Christian

converts for alienating China’s traditional gods and causing them to punish the

land and its people.[6]”

Both the Taiping Rebellion and the Boxer Rebellion rose from Chinese

frustration, but while the Heavenly Kingdom directed their wrath at the demonic

forces of the Qing, the Boxers believed foreigners were the source of their

pain.

| Boxers |

While both uprisings rose from among

the Chinese peasant class, both authors view the greed of Western imperialism

and the intrusion of Christian missionaries as instrumental in both

revolutionary movements. Particular notice points to the missionaries as

instruments who disturbed the social fabric of Chinese life. Chinese Christians

refused participation in the cultural and religious customs of village life

thereby causing division within the community. Practices such as ancestor

worship, long common among the Chinese for centuries became labeled as a form

of idolatry and rejected by Chinese Christians. For many, the rejection of long-held

customs was a rejection of Chinese culture and identity.[7]

For Preston, insensitivity to Chinese customs from missionaries led to the rejection

of Chinese Christians by the larger community and an enraged peasant class.

The origins of the Taiping Kingdom

rose not from the vexation of foreign influence but from the rigidity of the Qing

social system. But Spence lays blame at missionaries who intruded into Chinese

culture with little understanding of the culture and civilization. Many

missionaries concern themselves with their individual missions and numbers

rather than the impact of their message. The Taiping Rebellion does provide a

case study regarding the rapid spread of ideas and the ways in which the use of

religion can point to revolutionary movements. While both authors view foreign

interference as a cause of both rebellions, the inflexibility and seclusion of

the Manchus from the population also bear responsibility for the violence. Current

Communist Chinese rulers also possess rigidity in dealing with citizens who

fail to conform to Communist standards. But unlike the Qing, it remains to be

seen if the failure to respond to the needs of China will lead the Communists

to the same doomed path.

|

| China from Geology.com |

[1]

For a good treatment of the

Opium Wars see: W. Travis Hanes III and Frank Sanello, The Opium Wars (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2002)

[2] Jonathan D. Spence, God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly

Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996),

88.

[3]

For an academic treatment

of the Boxer Rebellion see: Joseph W. Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Rebellion, (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1987)

[4] Diana Preston, The Boxer

Rebellion: The Dramatic Story of China's War on Foreigners that Shook the World

in the Summer of 1900 (New York: Berkley Books, 1999), 22-23.

[5] Ibid., 24.

[7]

Ibid., 26.